unit 6, shakespeare’s king lear

meeting 1: the beginning of 1.1

Before we begin with the first scene of King Lear, we will spend just a few minutes discussing the origins of drama as well as the distinction between diegesis and mimesis. What do you know about Shakespeare? What do you know about his plays? What do you know about this play?

King Lear is a unique play among Shakespeare’s tragedies in many ways as we’ll see. The first way in which it is unqiue is that it is the only play (other than The Winter’s Tale) that begins with the play’s generic catastrophic moment: Why might the dramatist see this as valuable?

Recall the Gospel from mass the other day: 20 Then Jesus entered a house, and again a crowd gathered, so that he and his disciples were not even able to eat. 21 When his family[b] heard about this, they went to take charge of him, for they said, “He is out of his mind.” 22 And the teachers of the law who came down from Jerusalem said, “He is possessed by Beelzebul! By the prince of demons he is driving out demons.” 23 So Jesus called them over to him and began to speak to them in parables: “How can Satan drive out Satan? 24 If a kingdom is divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand. 25 If a house is divided against itself, that house cannot stand. 26 And if Satan opposes himself and is divided, he cannot stand; his end has come. 27 In fact, no one can enter a strong man’s house without first tying him up. Then he can plunder the strong man’s house. 28 Truly I tell you, people can be forgiven all their sins and every slander they utter, 29 but whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will never be forgiven; they are guilty of an eternal sin.”

Each great scene in a play will revolve around a central conflict. The central conflict in 1.1 is Lear’s desire to give up power but inability to give up all of the things that come with power.

meeting 2: shakespearean prose/verse & 1.1-1.2

Today, after the vocabulary quiz, we’ll discuss the circumstances under which Shakespeare gives his characters verse and prose to speak. As you continue to read, pay attention to shifts between prose and verse as they often provide insight into the dynamics in the scene.

Why is Lear so cruel to Cordelia in the second half of 1.1? Is he being petulant by throwing the word “nothing” back at Cordelia, or is it coincidence?

What does Cordelia have to say about flattery and lying in her speech on page 15? And what of her prophetic line to her sisters: “Time shall unfold what plighted cunning hides;/Who covers fault, at last with shame derides”?

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

I’d like you to try your hand at reading the next scene, Act 1 scene 2. Prepare it for our next class. While reading, think about how Edmond and Edgar’s dialogue compares to Gonerill and Regan’s dialogue in the previous scene. If you want also to watch the Royal Shakespeare Company production, you may log in to Drama Online Library with strakejesuit, crusaders. It will help to watch the scene. It begins at 18:45.

meeting 3: machiavelli & 1.2-1.3

“Everyone sees what you appear to be, few experience what you really are.”

“If an injury has to be done to a man it should be so severe that his vengeance need not be feared.”

“The lion cannot protect himself from traps, and the fox cannot defend himself from wolves. One must therefore be a fox to recognize traps, and a lion to frighten wolves.”

“The first method for estimating the intelligence of a ruler is to look at the men he has around him.”

“There is no other way to guard yourself against flattery than by making men understand that telling you the truth will not offend you.”

“Never attempt to win by force what can be won by deception.”

“It is much safer to be feared than loved because ... love is preserved by the link of obligation which, owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity for their advantage; but fear preserves you by a dread of punishment which never fails.”

Pick a quote from “The Prince”, above, and a character from King Lear who might respond to that quote. How might that character respond?

1.2: What parallels do you see between 1.1 and 1.2? How does Edmond manipulate his father so quickly? Is it believable that he might be convinced so quickly?

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Read the first part of 1.4, stopping before Gonerill’s entrance on page 41.

MEETING 4: shakespeare’s fools & 1.3-1.5

We’ll talk today about the convention of the Fool in Shakespeare’s plays with particular focus on the license they have to criticize the behavior of those they serve. In his first scene the Fool makes about 25 jokes, many of them puns, all of them intended to show Lear’s mistakes. There seem to be 4 subcategories of criticism:

1) It was stupid to give up power and wealth. 2) It was really counterproductive to have banished Cordelia. 3) It was dumb to put yourself at the mercy of your evil daughters. 4) It was all caused by the fact that you act without thinking.

What’s the difference between the loyalty of the Fool and the loyalty of Kent?

How have your sympathies for Lear changed, if at all, by the end of the Act?

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Read 2.1.

MEETING 5: comedy/tragedy & 2.1-2.2

Mosaic depicting theatrical masks of Tragedy and Comedy, 2nd century AD, from Rome, Palazzo Nuovo

Comedy and tragedy don’t merely delineate happy and sad; more precisely, comedy and tragedy refer to the narrative structure of a play, the way in which the play’s dramatic conflicts resolve. A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet are largely the same play, but one is a comedy and one is a tragedy because of the way the conflicts resolve: If Juliet wakes 30 seconds earlier, the play is a comedy; if the lovers don’t discover they’ve been in love with the wrong person, they just might die. Comedies end happily in marriage; tragedies end unfortunately in death. Shakespeare, however, knows that good drama blurs of the lines of these genre and uses elements of each in many of his plays.

Today we’ll review the play’s first Act and work through the first few scenes of Act 2.

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Prepare for a quiz on Act 1.

MEETING 6: What’s in a word? & 2.1-2.2

After the quiz today, I’ll set your next writing assignment, which is a short one, designed to get you to think about the function of a single word in the play so far. We’ll do our best to finish with the second scene of Act 2.

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Prepare for our next vocabulary quiz and finish your short writing assignment.

MEETING 7: the bedlam beggar & 2.3-2.4

Today, after the vocabulary quiz, I’ll set the context for Edgar’s means of hiding. We’ll then look at his first of many soliloquies.

2.4 is in my top 10 scenes from Shakespeare’s plays. It’s an extraordinarily sad descent into madness. We need to decipher whether Lear himself is or Gonerill and Regan are to blame for his descent. Does Lear make things worse for himself? How is the Fool prophetic at the beginning of the scene?

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Finish reading Act 2 and 3.1

MEETING 8: sh’s favorite question & 3.1-3.3

A total of twenty scenes throughout all of Shakespeare’s plays begin with a line I’ve dubbed Shakespeare’s favorite question: “Who’s there?”. Hamlet begins with it; Othello ends with three instances of it; Macbeth’s Porter asks it three times in one speech. In forty plays, it appears fifty times. And while you might say—‘Well, of course, Mr. Kubus. “Who’s there?” is a common question and a practical one in a staged drama. Why wouldn’t it appear that often?’—I’d like to explore both the dramatic and thematic functions of the question in any given play, in this play, and in this scene.

One of Shakespeare’s most famous scenes, 3.2, depicts the weather mirroring Lear’s madness. Why is that particularly appropriate given what many characters argue about nature?

How is the fool different in 3.2 than he was before? What do we learn in this scene about the nature of his foolery?

There are three parts of Lear’s diatribe in 3.2. We’ll move through all three today in class before watching our production’s version of the scene.

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Finish reading Act 3. Turn to page 132 in our text. Respond to exercise 3: Madness. Skip points 1 and 4. Do points 2 and 3: “Pick out…” and “Then choose…”.

MEETING 9: the 4 humors & 3.2-3.7

Today we’ll begin by introducing some Early Modern Mental Health Tips. Are everyone’s humors in balance?

Next, we’ll begin on page 103: Note Lear’s call back to 1.1.

In the remainder of Act 3, Shakespeare begins alternating between Lear and Gloucester, the play’s two old men. What is Shakespeare’s dramatic intent in alternating these scenes as he does? What thematic point might he be trying to highlight?

Is there any intelligibility in the way Edgar manifests Tom’s madness?

At the end of class we’ll review some of the more important quotes from Acts 2 and 3.

MEETING 10: 4.1-4.3

After the quiz today, we’ll turn to Act 4. Just as most penultimate episodes of a season of television contain some of the most important moments, the fourth act of a Shakespeare play reaches a climax. The end of Act 4 is largely considered to be a masterpiece. Today in class, we’ll move through scenes 1-3. Why does Edgar continue to keep his identity from his father?

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Finish reading Act 4.

MEETING 11: 4.3-4.6

Who is vying for power in Britain at this point in the play? I think it’d be helpful to step back and first consider the various narrative threads and how they’re tangling.

Scenes 5 and 6 of King Lear stand tall above most other scenes in the history of drama not only for their emotional impact but also for the contrast they draw toward one another. Of course they are both scenes of recognition, of knowing again, of becoming reacquainted, but what do you see as the key distinctions between the recognitions of Gloucester/Edgar (even though Gloucester doesn’t quite know entirely who Edgar is), Lear/Gloucester, and Lear/Cordelia? They are also scenes of miracles, of impossible reunions that take shape, or at least that’s how they’re framed in the text. What does Shakespeare want us to see in putting these two scenes right next to each other?

Sift through Lear’s madness. Find

(1) sorrow.

(2) humor.

(3) wisdom through suffering.

What’s the dominant emotion in King Lear when he first sees Cordelia? Is it shame? Is it joy? Why?

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Read 5.1 and 5.2. Leave the last scene for us to work through together in our next class.

MEETINGs 12/13: Act 5

Samuel Johnson said of the final scene of King Lear that it’s too sad to perform. As we work through the scene, ask yourself why Johnson would’ve made this claim.

Do you think the Lear of Act 5 is too different from the Lear of Act 1? If not, what has it taken to get him from point A to point B?

In 5.3, after Cordelia’s first line, she’s silent for the rest of the play. Of this and the general treatment of Cordelia, scholar Kathleen McLuskie says, “Cordelia’s saving love, so admired by critics, works in the action less as a redemption for womankind than as an example of patriarchy restored.” What do you think? Does McLuskie have a point? Can the same rationale be applied to the poor and disabled—that is, does the fact that the poor lose their voice in the play simply restore the monarchy as it was at the beginning of the play? Do you think Shakespeare is conscious of this?

Kent asks near the very end of the play, “Is this the promised end?” Is it? Did Shakespeare break a contract? Is the sadness to much?

Are you satisfied with the political resolution of the play? Is it appropriate? Why or why not?

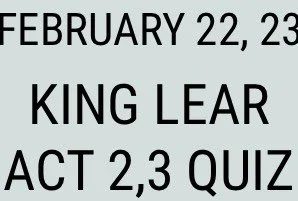

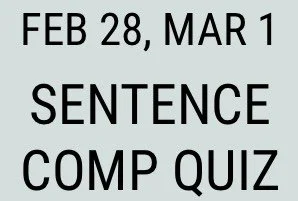

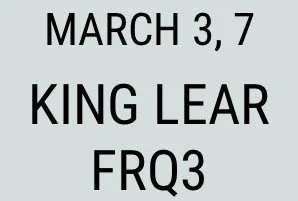

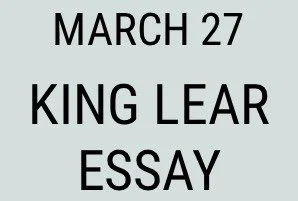

due DATES

syllabus

cyclical vocabulary and sentence composition assignment

CURRENT TEXTs TO HAVE DAILY

Moby-dick central

You’re undertaking the reading of the greatest work of American fiction and one of the world’s greatest works of art. It’s a project that’ll span the entirety of the year, completing the reading outside of class and in addition to your other regular assignments. It’s an undertaking to read this novel, to be sure, but it need not be arduous if you’re disciplined.

An undertaking, yes, but that does not mean you should simply set it down and walk away when you hit a tough or a boring chapter. It’s a rewarding book to those who work the hardest and put in the time it requires. This section of the course page provides you the tools you’ll need to work the novel through to its completion.

Here is a handy document you might consider printing and having with you while you read: Allusions in Moby-Dick

You may find it useful to use the audio recordings from The Big Read; each chapter has a special guest reading it. Listening along will help, especially at the beginning. The readers are (mostly) excellent at capturing the tone of each chapter. As you read, seek out and consider the following concepts:

Water meditations and man's attraction to water, Ishmael's curiosity about and tolerance for human motivation, The quest, The nature of God and man, Finding and losing the self (Narcissus), Parallels between land and sea, Civilization and "savagery", cannibalism, Biblical echoes and references: Jonah, Job, Ahab, Elijah, Ishmael, etc., Monomania and madness, the value of religion, the value of community

“There are certain queer times and occasions in this strange mixed affair we call life when a man takes this whole universe for a vast practical joke, though the wit thereof he but dimly discerns, and more than suspects that the joke is at nobody’s expense but his own.”