unit 1, amor towles’ a gentleman in moscow

“I’ll tell you what is convenient,” he said after a moment. “To sleep until noon and have someone bring you your breakfast on a tray. To cancel an appointment at the very last minute. To keep a carriage waiting at the door of one party, so that on a moment’s notice it can whisk you away to another. To sidestep marriage in your youth and put off having children altogether. These are the greatest of conveniences, Anushka—and at one time, I had them all. But in the end, it has been the inconveniences that have mattered to me most.”

meeting 1: literary constraint

Welcome. Today we’ll talk briefly about the nature of this course and how to do well, my expectations, my hopes for you. But first…

Counterintuitively, literary constraint opens doors for a writer. What’s literary constraint or constrained writing? Why do author’s use constraints? What are some examples of constrained writing? What are the constraints Towles puts on himself when he sits down to write A Gentleman in Moscow?

In this class, though, we never talk about literary form or technique out of the context of theme. That is to say, form always connects to a literary work’s larger implications, interpretations, and ideas. So, let’s use some of our time today to think about how the constraints of A Gentleman in Moscow amplify some of the novel’s themes.

Homework: (1) Familiarize yourself with the course website—this page, the Policies page, and the Writing Center. It’s up to you to know the resources you’ve available to you. Study these pages.

(2) Register on turnitin.com: Class ID: 39619465 Enrollment Password: Magis

(3) Post your summer reading essay to turnitin.com by 8 PM on the night of your first class, either the 17th or the 18th.

(4) Think: What kinds of restraints were put on your self-selected novel? Brainstorm in your notebook. Be prepared to share tomorrow.

meeting 2: towles’ characterization

Today we’ll begin with a review of last class. What kinds of constraints were put on your self-selected text? Do you see a thematic connection? I’ll ask you to share with a partner and then with the large group.

Next, let’s turn back to A Gentleman in Moscow, with an eye to discovering Towles’ techniques for characterization. To begin, let’s make a simple list of the Count’s virtues and vices. Is there any overlap? Is the Count an archetype, or is he something more complicated and human? Let’s explain with passages.

When we think about literature, one of the things we often want to do is discover whether or not a main character achieves any sort of wisdom or comes to a new understanding or changes in a certain way or grows into something more whole than what he or she once was. Is this the case with the Count? Is he more whole by the end of the novel? In what ways? Does he go on a journey as do so many of the characters he and the narrator reference (Odysseus, Dante, Robinson Crusoe)? What does the accordion structure of the novel suggest about his growth? If structure aids characterization, what are we to learn about the Count in the novel’s symmetrical moments?

What about the minor characters? Are they archetypes, existing in the novel merely as foils to teach us something about the Count? Which of these minor characters most affect his understanding of some of the novel’s meaty subjects like love, family, dignity, personal agency, duty & desire, or purpose?

Our close-reading passage for today:

Lastly, what questions did you come away with from last time about how this class will run?

Homework: (1) Study your notes on the novel. You’ll have a quiz at the beginning of our next class.

meeting 3: quiz / narrative voice

After the quiz, we’ll consider the narrative voice of A Gentleman in Moscow. As we’ll see this year, an author’s choice of narrator is the single most important decision he or she makes before writing their novel, and it’s one of the most important jobs of the student of literature to consider the narrative voice carefully, its characteristics, its quirks, its effects, its reliability, its bias, its point of view. Though we will spend the rest of today thinking about narrators, our short fiction unit and subsequent novel units will offer us more time to consider them in much greater detail.

Let’s begin by thinking about different types of narrators we’ve seen in the past and then the narrator in Towles’ novel. Is it always the same? Does the point of view ever shift? At what times? Why? How and why does Towles layer in a second narrative voice? What are the characteristics of that second narrative voice?

With whom does the narrator side in the novel? Is it always clear? Do you detect any unreliability? How so?

We’ll finally consider different types of narrative style used in Towles’ novel: direct, indirect, and (everybody’s favorite) free-indirect.

Our close-reading passage for today:

Homework: (1) Think: What kind of narrator did the author of your self-selected novel choose? Why is this narrator appropriate given the thematic nature of the book? Do you see any instances if free-indirect style? Brainstorm in your notebook. Be prepared to share tomorrow.

meeting 4: Critiques of the novel

Objectively—yes, objectively—we can find ways to critique literature. Today I’ll ask you to evaluate the novel in the following domains:

Plot: Are the novel’s final events a product of the novel’s previous events? Look back at the poem at the beginning of the novel. Does it hint at what would happen at the end? Or are there too many moments of deus ex machina?

Narrative Voice: Are there inconsistencies in the narrative voice that make reveals and twists make no sense?

Characterization: Are the characters flat for no reason? Do they all sound the same?

Tropes: Are the patterns that the novel borrows cliches?

But first, what does the novel do well? What does the novel do really well?

Our close-reading passage for today:

Homework: If you have not done so already: (1) Think: What kind of narrator did the author of your self-selected novel choose? Why is this narrator appropriate given the thematic nature of the book? Do you see any instances if free-indirect style? Brainstorm in your notebook. Be prepared to share tomorrow. (2) Perform as objective of an evaluation of your self-selected novel as you’re able using the criteria from class.

meeting 5: theme in a gentleman in moscow

“I fear I have done you a great disservice, Sofia. From the time you were a child, I have lured you into a life that is principally circumscribed by the four walls of this building. We all have. Marina, Andrey, Emile, and I. We have ventured to make the hotel seem as wide and wonderful as the world, so that you would opt to spend more time in it with us. But your mother was perfectly right. One does not fulfill one’s potential by listening to Scheherazade in a gilded hall, or by reading the Odyssey in one’s den. One does so by setting forth into the vast unknown—just like Marco Polo when he traveled to China, or Columbus when he traveled to America.”

Today is our first day of writing instruction for the year. We’ll review the parts of the opening paragraph, using strong samples as models. Here’s the model essay’s thesis. Here are a few more of your own.

Once we review thesis statements, I’d like to back to A Gentleman in Moscow and develop three thesis statements as a group on three subjects in the novel. Here’s the handout.

Homework:

The revision of your summer essay is due right after Labor Day weekend, either the 5th or the 6th of September, depending on when you have class. Post your essay to turnitin.com by 8am on your due date. Bring a stapled and properly formatted paper copy of the essay with Works Cited page. You’ll submit in class. The word count will be a range of 1200-2000. Should you finish before Labor Day weekend, you’re welcome, of course, to turn in the revision early, and I’ll gladly grade it over the long weekend.

meeting 6: draft revision 1

At the beginning of today’s class, I’ll set the first vocabulary and sentence composition assignment. Here are samples of the first patterns. Remember that you’re to look up the definitions of each of the adjectives to define a writer’s tone.

Today’s class explores the anatomy of an essay, using a structurally sound sample on Jane Austen’s novel Pride and Prejudice. In our dissection, we’ll find a strong opener, a rich thesis, a rock-solid structure, cogent thinking, good evidence, and a clear style. Today’s class is foundational for the rest of the year.

After, you’ll provide feedback on two sample body paragraphs, one on Crime and Punishment, one on Inferno.

meeting 7: draft revision 2

What do you remember from yesterday’s class?

We’ll begin today with how you might extend your elaboration of a quote. I often hear from students that they don’t know what to say after they bring in a quote. I’ll try to help you with that today by looking at Lydia’s quote in the essay from yesterday’s class.

Let’s compare this draft to its revision on the right.

Homework: Carefully read Hemingway’s “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place” in the Hemingway anthology, pages 288-91.

due DATES

The revision of your summer essay is due right after Labor Day weekend, either the 5th or the 6th of September, depending on when you have class. Post your essay to turnitin.com by 8am on your due date. Bring a stapled and properly formatted paper copy of the essay with Works Cited page. You’ll submit in class. The word count will be a range of 1200-2000. Should you finish before Labor Day weekend, you’re welcome, of course, to turn in the revision early, and I’ll gladly grade it over the long weekend.

community time conversations

CURRENT TEXT TO HAVE DAILY

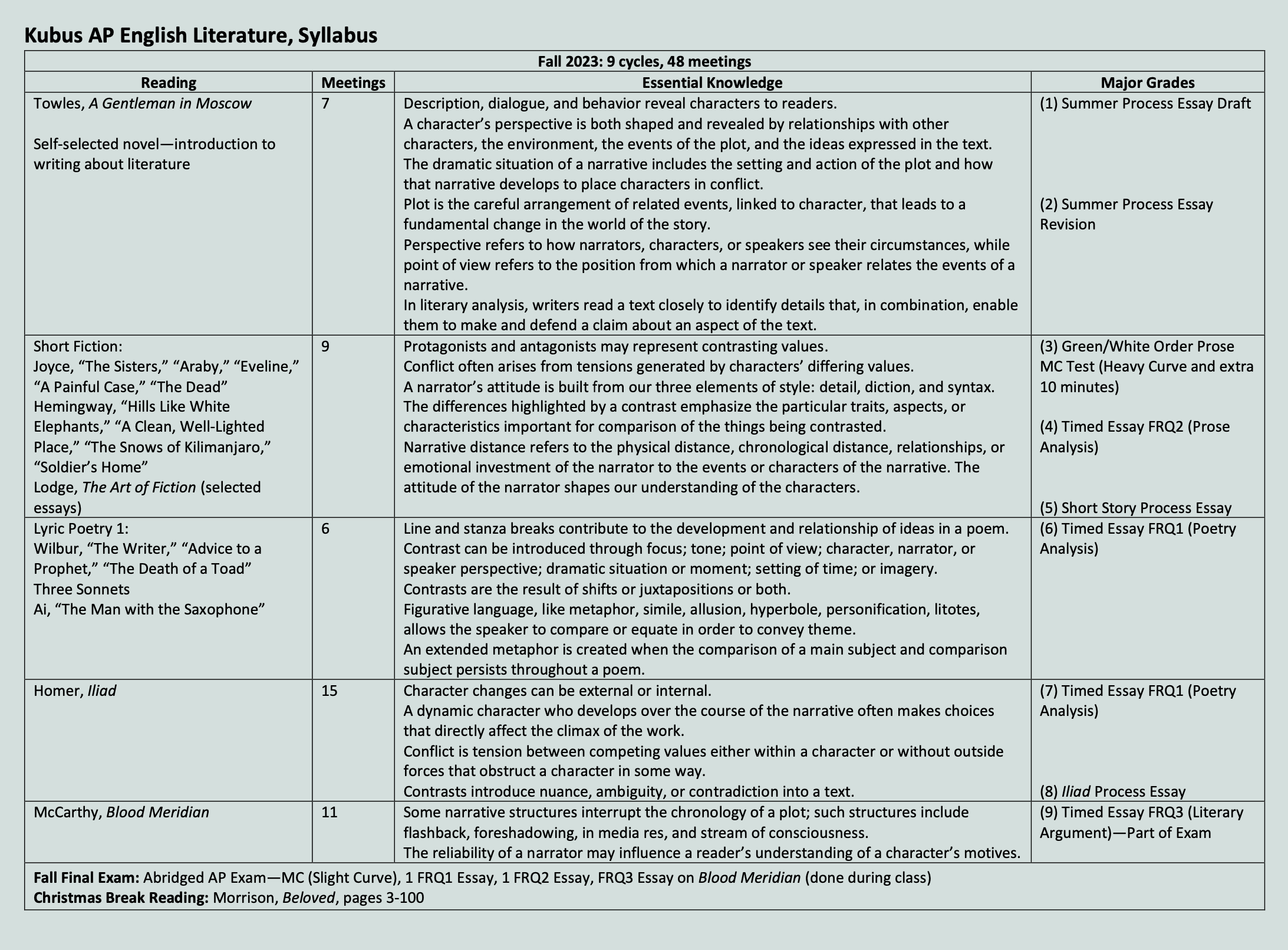

syllabus

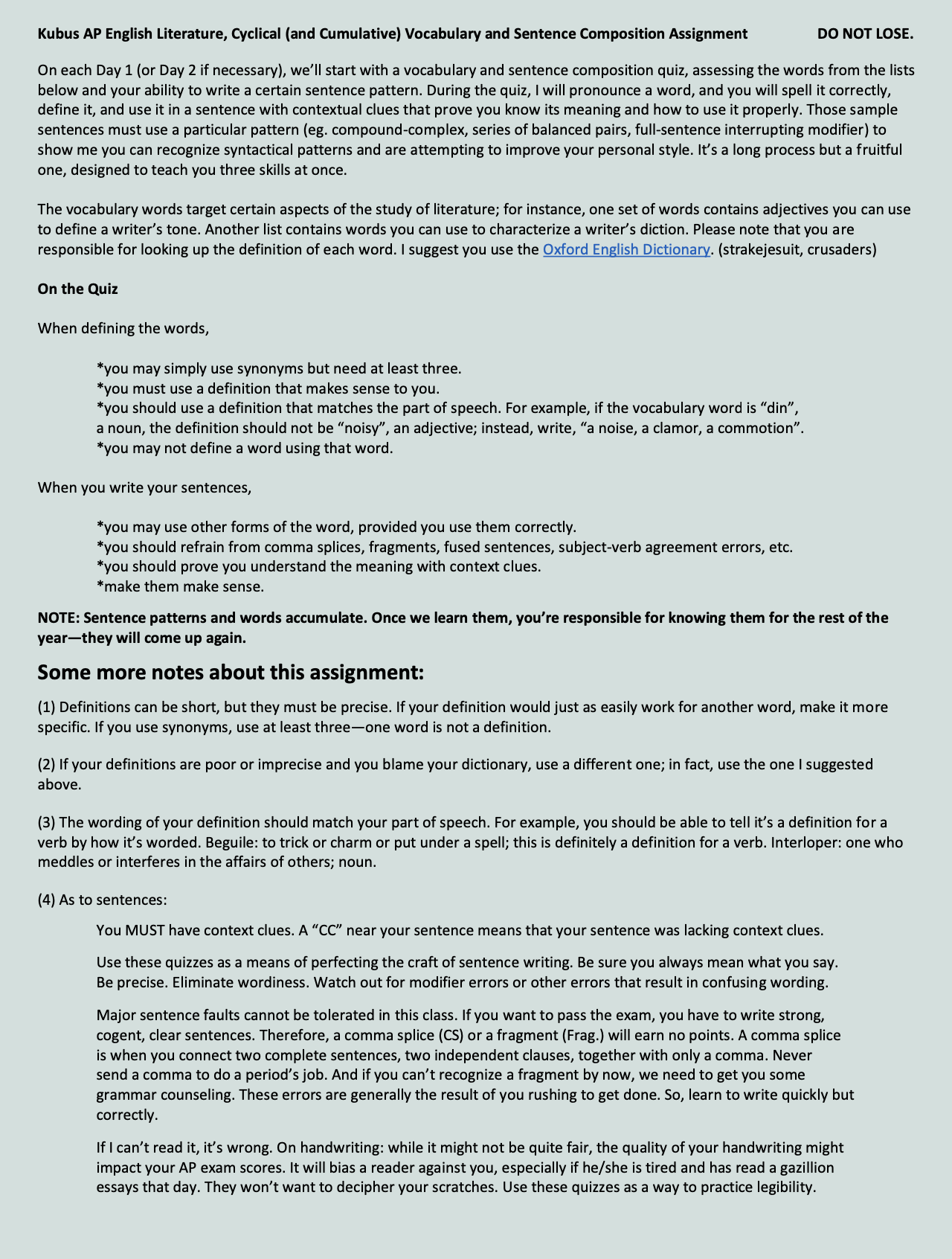

cyclical vocabulary and sentence composition assignment

upcoming units

writing assignments

2022-2023 UNITS

war and peace central

It seems even Tolstoy didn’t quite know what War and Peace is: “It is not a novel,” he said, “still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle. War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express, in the form in which it is expressed.” And yet, it’s the first title we think of when we think of some of the greatest or most famous novels ever written. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s innovative: it plays with multiple languages, moves from battlefields to palaces to country estates, combines historical figures like Napoleon and Kutuzov with fictional characters like Bolkonsky and Rostov, folds in bloody battles to scenes of great personal strife and triumph, and changes narrators at will. That’s innovation. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s human: Tolstoy writes no archetypes, but people; no heroes, but soldiers; no villains, but sinners; no pillars of grace, but kind-hearted, flawed characters. That’s human. And whatever War and Peace is, it’s big: With almost 600—yes, 600—named characters, more than 1300 pages, multiple shifts in narrative voice, oscillations between scenes of aristocratic drama and the history of the Napoleonic Wars and some of Tolstoy’s personal philosophy, it’s no wonder Henry James famously called War and Peace “a big, loose, baggy monster.”

Once a month, a small group of us will have a meeting to discuss the next section of the novel, spending a few consecutive days after school with conversation, food, and drink. I hope it’ll be something you really enjoy despite the obstacles of the novel. But don’t let those obstacles prevent you from working through it. Look, I get it: the names are hard, and like I said, there are a lot of them. And look, I get it: Looking at the footnotes to translate the French is annoying. And look, I get it: there are some parts that are just plain dull. It’s okay. Sometimes long-form fiction will be like that. But you’ll do your work, anyway, like the great student and person you are. There are many reasons to set this book down and move on with your life, but there are more reasons—some you may not understand for a few years—to continue working your way through. It’s a work of art filled with beautiful characters, intricately woven threads of plot, thrilling scenes, compelling relationships, people to root for and against. The natural barriers of the novel are nothing compared to the reward on the other side. You’ll be just fine—better than fine, really. And you’re reading in a community of like-minded readers with great opinions to encourage you through it.