unit 3, lyric poetry 1

meeting 1: from prose to poetry — Santiago baca’s “Green chile” and blanco’s “mother country”

What is a lyric poem? How does poetry differ from prose? These are the two questions we’ll try to answer today, diving into two poems: Jimmy Santiago Baca’s “Green Chile” and Richard Blanco’s “Mother Country”.

Homework: Read Richard Blanco’s “Shaving”. Mark it up as we did in class. What two associations do you make in response to the prompt at the top of the page? No need to write a thesis; just identify the complexity.

meeting 2: IDENTIFYING SHIFTS WITH RICHARD WILBUR

In today’s class, after we review “Shaving,” we’ll look at 2 poems from 20th-C American poet Richard Wilbur: “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World” and “Advice to a Prophet”. Our goal in both poems is to identify tonal shifts and purposeful movements on the part of the speaker.

We’re going to travel lightly for now in terms of literary terminology, sticking just to structure, tone, diction, and syntax, as well as imagery and figurative language.

“Plato, St. Teresa, and the rest of us in our degree have known that it is painful to return to the cave, to the earth, to the quotidian; Augustine says it is love that brings us back.”

We’ll work “Love Calls Us to the Things of This World” together as a group; you’ll tackle “Advice to a Prophet” in a small group; then, for homework, you’ll read “The Writer” and “The Death of a Toad” on your own.

Homework: Read “The Writer” and “The Death of a Toad”. Mark it up as we did in class, identifying any tonal shifts and movements in the poem. On the bottom of the page, write a thesis for a poetry analysis responding to the following prompt: Explain how formal elements, such as structure, tone, syntax, diction, and imagery reveal the speaker’s COMPLEX response to (1) his role as a father and (2) the death of the toad.

meeting 3: dickey, “the bee” & poetry mcq

Sit today with your CHAVRUSA.

Warm-up poem: James Dickey’s “The Bee”. Who’s the speaker? What’s the conflict? Where do you sense shifts in perception?

On to the main business of the day: “Death of a Toad” and “The Writer”. How did you do with your two poetry analysis thesis statements? Wherein lies the complex response in each poem? Share with your chavrusa.

We’re going to use “The Writer” and “Advice to a Prophet” to introduce poetry MCQs. I have a set of questions on each of Wilbur’s poems that you and your chavrusa can struggle through together. We’ll go over the answers afterward.

Let’s check in about your short story process essay at the very end of class.

Homework: Prepare for your next vocabulary and sentence composition quiz. Remember the sentence pattern is paired construction.

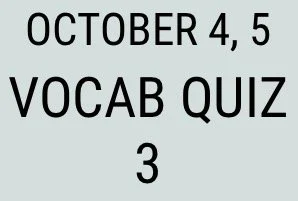

meeting 4: vocab quiz 3; Donne’s HolY sonnets 1

After the quiz today, we’ll turn to one of John Donne’s so-called Holy Sonnets: “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.”

How does a sonnet tend to work structurally? Why do poets use rhyme, rhythm, and metrical patterns? How do those formal features of poetry underscore the thematic elements of poetry?

Homework: Work through “Death, be not proud,” the other of Donne’s Holy Sonnets that I included in your poetry reader. Finish: “This poem dramatizes the conflict between…” How does the final irony in the poem add meaning? Break up the poem into its stanzaic pattern in order to locate the individual thoughts. Are there figurative or imagistic elements you find striking? How do they create meaning?

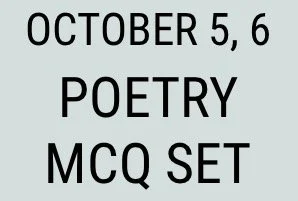

meeting 5: donne’s holy sonnets 2; poetry MCq

We begin today with the second of Donne’s “Holy Sonnets”: “Death, be not proud.” How did the final irony at the end of the poem add meaning? Were you able to find the individual thoughts from the stanzaic pattern? Which figurative and/or imagistic elements did you find most relevant to an interpretation of the poem?

Now to assessment: 21 Poetry MCQ, half on a poem you’ve seen, half on a sonnet you’ve not.

Homework: Next week we begin our longest unit of the year—Homer’s Iliad. Please read Book 1 in its entirety. THINK about the following as you read.

(1) According to the first 8 lines, what will this poem be about?

(2) What accusations do Achilles and Agamemnon level at each other? Do you think these charges are just?

(3) Who do you think is in the right in this quarrel? Who do the Achaeans think is in the right? Why? Why do you think Achilles and Agamemnon fail to take Nestor’s advice?

(4) What kind of people do you think Agamemnon and Achilles are?

(5) In what senses is Agamemnon more powerful than Achilles?

(6) What do you think the heroes in the Iliad are fighting for? Do the heroes seem to like fighting? What do the gods seem to care about? How are their concerns like / unlike the heroes' concern for honor and glory?

due DATES

CURRENT TEXTs TO HAVE DAILY

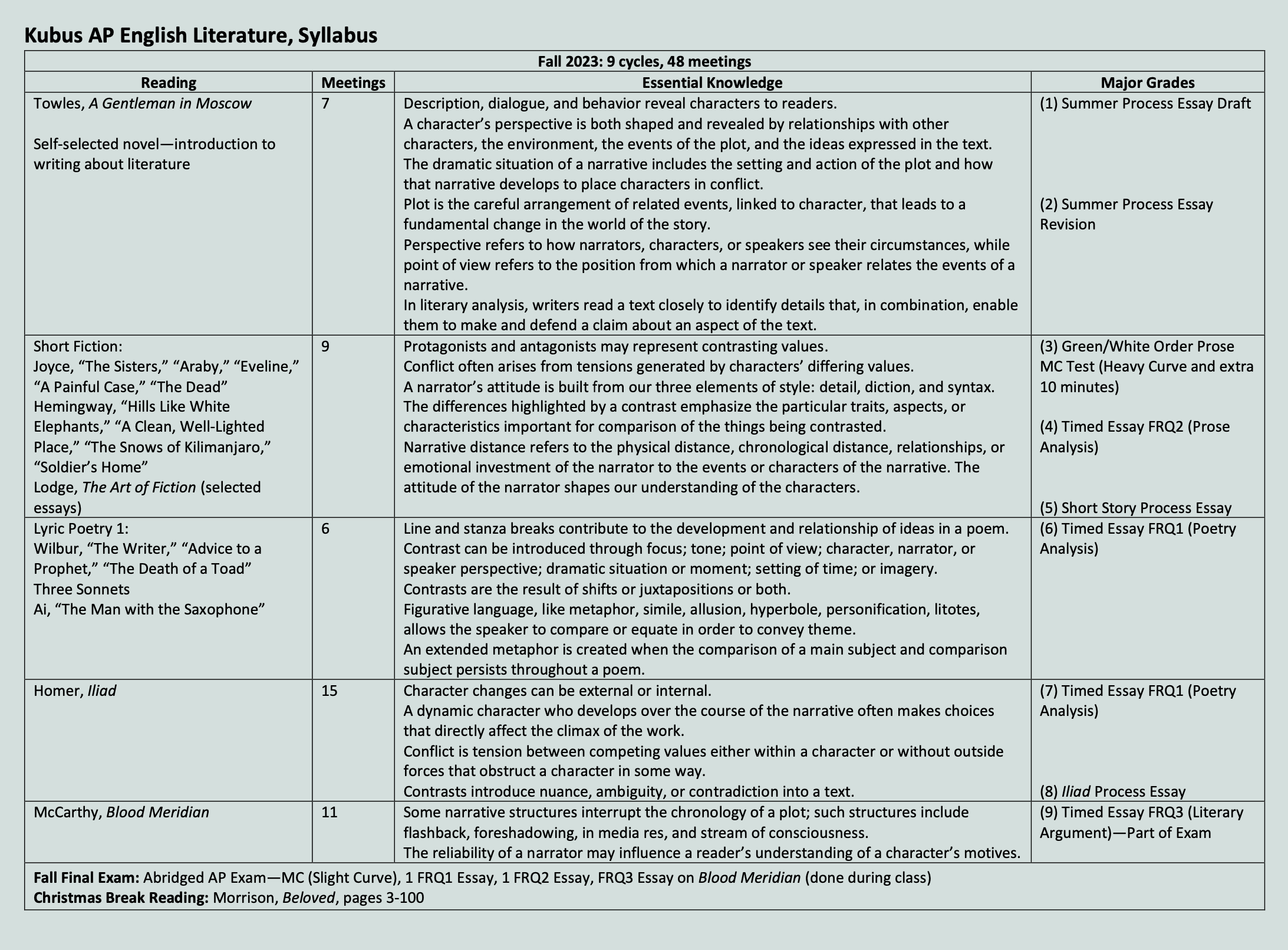

syllabus

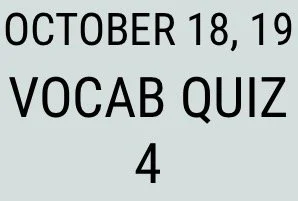

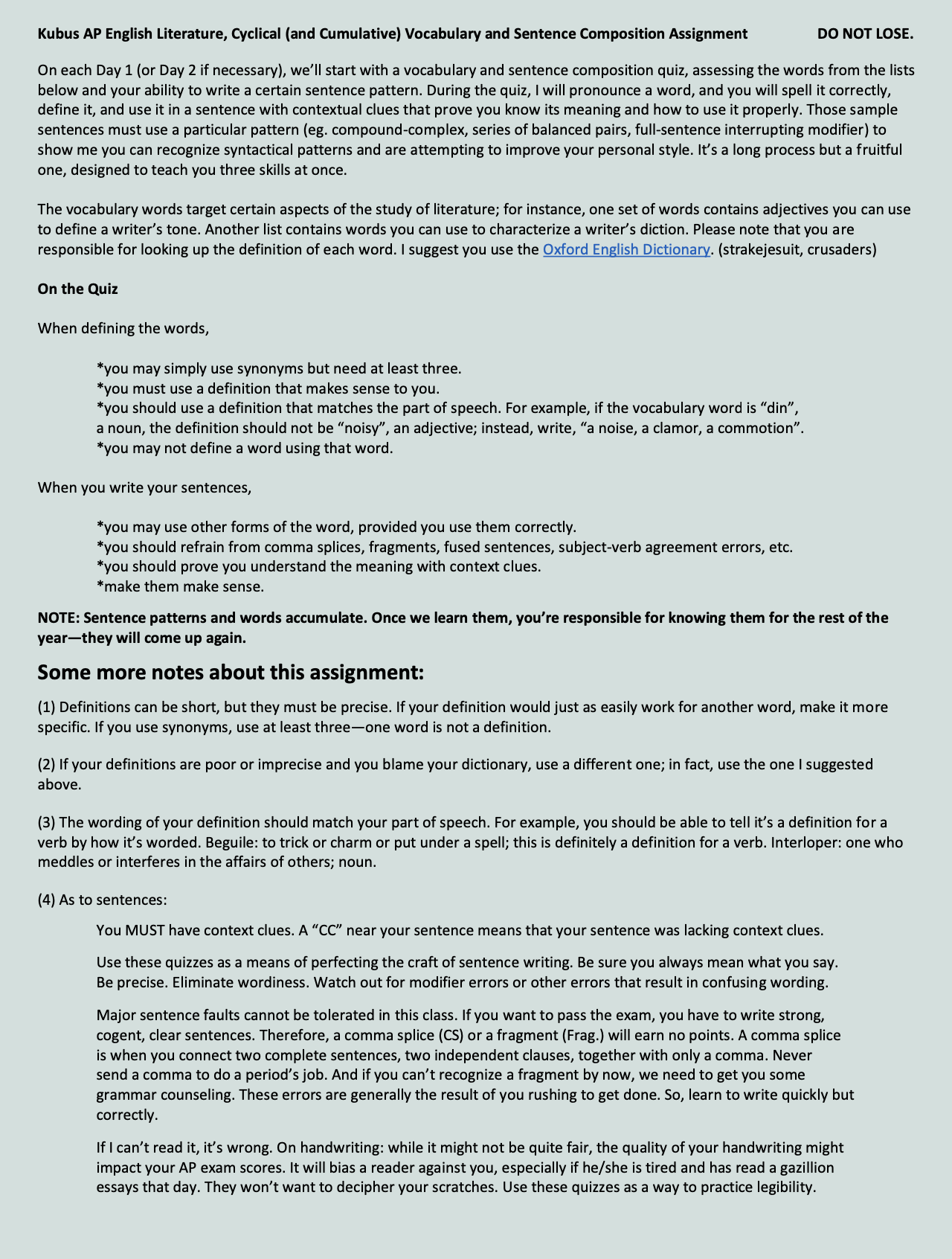

cyclical vocabulary and sentence composition assignment

2023-2024 units

writing assignments

2022-2023 UNITS

war and peace central

It seems even Tolstoy didn’t quite know what War and Peace is: “It is not a novel,” he said, “still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle. War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express, in the form in which it is expressed.” And yet, it’s the first title we think of when we think of some of the greatest or most famous novels ever written. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s innovative: it plays with multiple languages, moves from battlefields to palaces to country estates, combines historical figures like Napoleon and Kutuzov with fictional characters like Bolkonsky and Rostov, folds in bloody battles to scenes of great personal strife and triumph, and changes narrators at will. That’s innovation. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s human: Tolstoy writes no archetypes, but people; no heroes, but soldiers; no villains, but sinners; no pillars of grace, but kind-hearted, flawed characters. That’s human. And whatever War and Peace is, it’s big: With almost 600—yes, 600—named characters, more than 1300 pages, multiple shifts in narrative voice, oscillations between scenes of aristocratic drama and the history of the Napoleonic Wars and some of Tolstoy’s personal philosophy, it’s no wonder Henry James famously called War and Peace “a big, loose, baggy monster.”

Once a month, a small group of us will have a meeting to discuss the next section of the novel, spending a few consecutive days after school with conversation, food, and drink. I hope it’ll be something you really enjoy despite the obstacles of the novel. But don’t let those obstacles prevent you from working through it. Look, I get it: the names are hard, and like I said, there are a lot of them. And look, I get it: Looking at the footnotes to translate the French is annoying. And look, I get it: there are some parts that are just plain dull. It’s okay. Sometimes long-form fiction will be like that. But you’ll do your work, anyway, like the great student and person you are. There are many reasons to set this book down and move on with your life, but there are more reasons—some you may not understand for a few years—to continue working your way through. It’s a work of art filled with beautiful characters, intricately woven threads of plot, thrilling scenes, compelling relationships, people to root for and against. The natural barriers of the novel are nothing compared to the reward on the other side. You’ll be just fine—better than fine, really. And you’re reading in a community of like-minded readers with great opinions to encourage you through it.