unit 4, homer’s iliad

meeting 1: the trojan legend and book 1

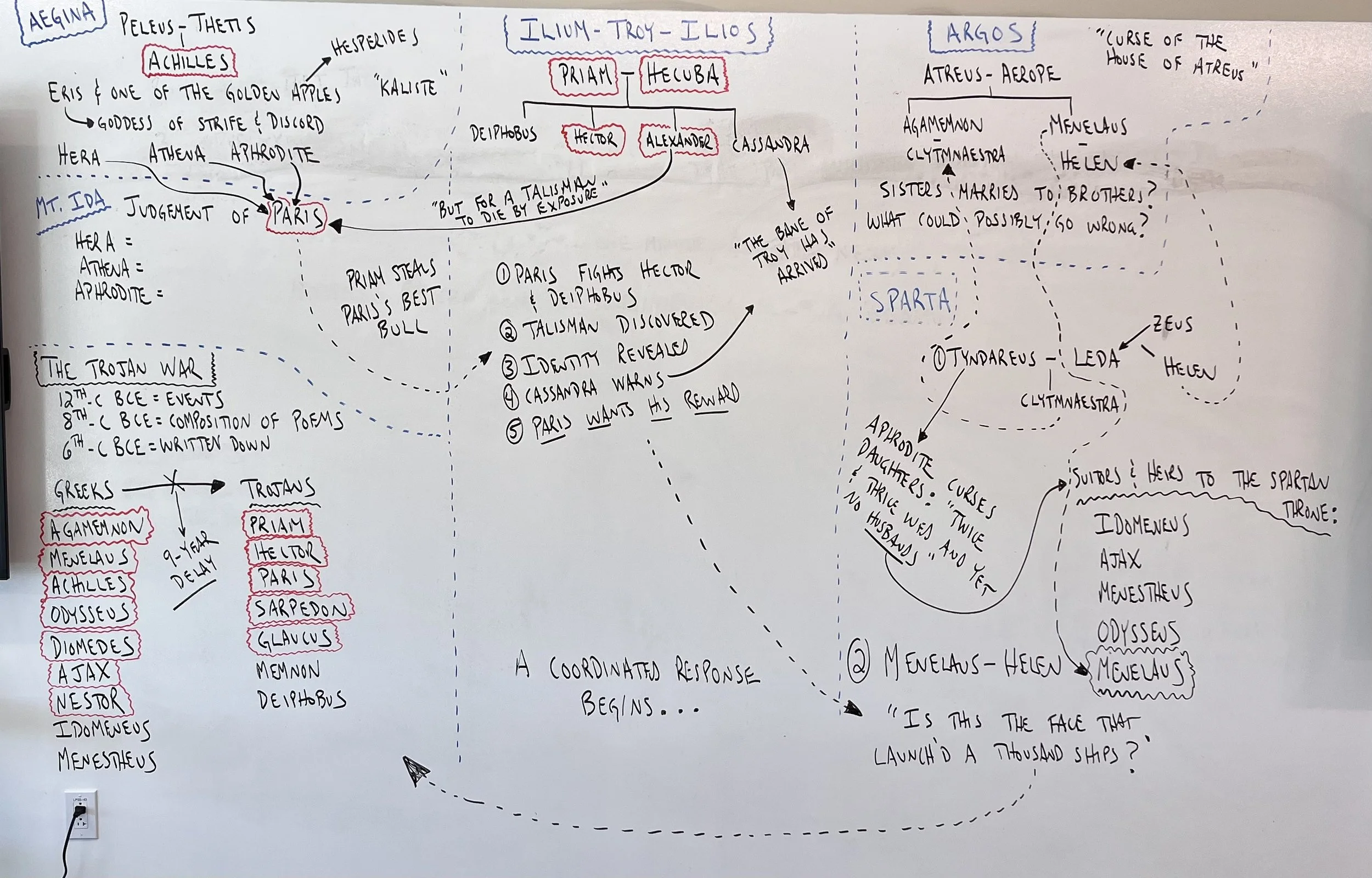

The events of Homer’s Iliad occur in a span that is less than a month in the 10th year in the Trojan War. So what was the Trojan War, and how did it start? In today’s Homeric mini-lecture, I’ll give you my best attempt at a retelling of the so-called Trojan Legend.

During most of today’s class, we’ll move through Book 1: According to the first 8 lines, what will this poem be about? What accusations do Achilles and Agamemnon level at each other? Do you think these charges are just? Who do you think is in the right in this quarrel? Who do the Achaeans think is in the right? Why? Why do you think Achilles and Agamemnon fail to take Nestor’s advice? What kind of people do you think Agamemnon and Achilles are?

Which passages stand out? Whose speeches are most memorable? Why?

Homework: Please read the following before our next class:

(1) These selections from Seneca's "On Anger". As you read Seneca, think about what makes you angry. How do you deal with it? Why, according to Seneca, should we avoid it?

(2) Books 2 and 3 of the Iliad. Reserve enough time. This is a long selection of the poem. Skip Book 2, lines 522-872: In a passage known as the Catalogue of the Ships, the poet lists—yes, lists—the contingents of the Greek army and their leaders.

MEETING 2: kleos, timê, and books 2 & 3

Let’s begin today with Seneca. What individual lines from Seneca’s “On Anger” strike you, and for what reason? Paraphrase the point he makes. Are there points of his you’d like to call into question? Once we sufficiently consider Seneca in his own right, we’ll use “On Anger” as a lens text through which we might consider the first 3 books of the Iliad in a new way. About which specific parts of Books 1-3 would Seneca have strong feelings?

Today’s mini-lecture concerns Kleos and Timê, two concepts that shape much of the heroic code in the Homeric world. What are they? And what is the relationship between both? How does this new context reshape your understanding of a moment so far in the poem? This reliance on a strong heroic code is one example of Homeric cultural values.

Cultural Values: Work in your small group to make a list of 5 cultural values on display in the first 3 books of the poem. Have an example associated with each.

Books 2 and 3: What do you think Homer intends to show the reader (about Agamemnon's character, about the morale of the Achaeans, about Odysseus) in the scenes detailing Agamemnon's plan to test his troops and its result? Why do you think Homer included the episode of Thesites' abuse of Agamemnon and his chastisement by Odysseus? Why is it OK for Achilles to abuse Agamemnon but not OK for Thersites to disrespect him?

What is your initial response to some of the key Trojan figures: Priam, Hector, Paris, Helen?

Homework: Read Book 6—Skip Books 4 and 5: The truce is broken when the Trojan Pandarus, at Athena’s urging, shoots an arrow into the Greek ranks and wounds Menelaus. Battle is joined, and the Greeks, led by Diomedes, who wounds even Aphrodite and Ares, push the Trojans back.

On Monday, during CT, I’m holding a sentence boot camp for all who need it in 4321.

MEETING 3: epic as genre and book 6

Adam Nicolson, Why Homer Matters

Let’s begin with a quick review of some sentence patterns. Then I want quickly to compare these two openers from your SS essays.

In today’s Homeric mini-lecture, I’ll provide a few thoughts about EPIC:

(1) Epic poetry is a form of narrative poetry, usually telling the story of a great culture or a hero and his exploits. Epic comes from the word epos, which means utterance or word.

(2) Epic differs from the form of the novel in that the novel tends to be of a particular time and place while the epic lends itself to universality, a broad exploration of humanity writ large.

(3) Follows certain conventions foreign to us as modern readers.

(4) Adam Nicolson

Book 6 of the Iliad walks us into the walls of Troy and offers a fully developed picture of Trojan society, a society that finds itself caught in a war they never sought. This extraordinary book shows the oldest generation of Trojans—Priam and Hecuba—down through the newest generation of Trojans—Astyanax—suffering the consequences of a crime none of them committed. In class today, we’ll explore Book 6 in detail by looking at the Book’s structure, its individual scenes, and its interrelated moments:

(1) Menelaus’s guilt / Agamemnon’s ruthlessness (2) Diomedes and Glaucus’s old ties of xenia (3) An imbalanced exchange of armor (4) Hector and Hecuba (5) Athena’s Denial (6) Hector, Paris, and Helen (7) Hector, Andromache, and Astyanax (8) A simile for Paris

What do each of those narrative beats combine to create in Book 6?

Homework: Read Books 7 and 8. Prepare for your next sentence composition and vocabulary quiz.

MEETING 4: Vocab quiz 4 and (briefly) books 7 & 8

Before the quiz today, let’s wrap our discussion about epic and the very end of Book 6. Then, quiz.

Your words for next time and the periodic sentence.

How does a poetry analysis differ from prose analysis? What will your poetry analysis look like next week? Let’s practice with a passage from the Iliad.

Homework: Read Book 9, one of the most famous Books of the Iliad. It’s the so-called Embassy to Achilles. As you read, put those AP Lang rhetorical analysis skills to work: Which characters seem to be the strongest speaker of words? Who makes the most compelling arguments? Notice just how many great speeches there are for a potential poetry analysis!

MEETING 5: performance and composition; Book 9

Sit today with your CHAVRUSA.

In the earliest books of the Iliad, Achilles’s heroism stems from his extreme passion for violence and warfare, but in Book 9, we see Achilles’s heroism take a new shape: His insightful and philosophical efforts to understand himself add a layer of complexity to his character. To what thematic end?

Let’s take, for example, this extraordinary moment from Book 9, which may be the clearest expression of the Iliad’s central theme, the clearest expression of every-work-of-literature-ever’s central theme, the clearest expression of what may be a question for you in your own life. Think through with your chavrusa what Achilles is really asking here.

Achilles: “My mother Thetis, a moving silver grace,/Tells me two fates sweep me on to my death./If I stay here and fight, I’ll never return home,/But my glory will be undying forever./If I return home to my fatherland/My glory is lost but my life will be long,/And death that ends all will not catch me soon.”

Analyze Book 9 as a rhetorical situation. What does each of the speakers say to Achilles, and how does he say it? Do you find their arguments persuasive? Do you feel that Achilles' resistance is justified? Is there any change at all in Achilles' position at the end of Book 9?

Homework: During our next class, you’ll have the hour to write your next timed essay: Last time, you wrote a prose analysis; this time, you’ll write a poetry analysis. Because it’s the second timed writing, know the following changes apply:

(1) You’ll have no prior knowledge of the passage, and each class will have a different passage. (2) The AP score will more accurately reflect the 100-point scale. Row C remains bonus. (3) You’ll be reading the passage on your own, and it will now be your job to identify the complexity on your own. (4) Be more attentive to careful, thoughtful planning; careful, thoughtful sentences; careful, thoughtful structure that revolves around complexity NOT literary devices. (5) Neatness counts. (6) No questions.

MEETING 6: poetry analysis

Timed essay

Homework: Read Books 10, 11, and 12 of the Iliad. Most of you have our next class together on Wednesday, an asynchronous day. Use the time at home to complete that reading.

MEETING 7: asynchronous reading day

MEETING 8: books 10, 11, and 12

Today we will bring to bear all our knowledge of the poem so far (Books 1-12) to see if we can discover what Homer intends to show about war. Is it glorified? Is it to be judged? Is it just an inevitability that people are going to make war? In an essay about the Iraq War, Charlotte Higgins writes about American soldiers reading the Iliad in their preparation for battle: She makes a series of claims about she thinks the poem has to teach us about war: “It tells us that war is both the bringer of renown to its young fighters and the destroyer of their lives. It tells us about post-conflict destruction and chaos; about war as the great reverser of fortunes. It tells us about the age-old dilemmas of fighters compelled to serve under incompetent superiors. It tells us about war as an attempt to protect and preserve a treasured way of life. It tells us, too, about the profound gulf between civilian existence and life on the front line; about atrocities and indiscriminate slaughter; about war's peculiar mercilessness to women and children; about friendships and sympathies across the battle lines. It tells us of the love between soldiers who fight together. Most of all, it tells us about the frightful losses of war: of a soldier losing his closest companion, of a father losing his son.”

Book 10: What are the Greeks without Achilles?

Book 11: Why are a series of Greek heroes wounded?

Book 12: What does the exchange between Sarpedon and Glaucus have to teach us about heroism in war?

Homework: Prepare for your next vocabulary quiz. Read Books 16 and 17—Skip Books 13, 14, and 15: “The Longest Day” continues. Poseidon rallies the Greeks. The Greek Heroes Idomeneus and Meriones meet behind enemy lines, and then Idomeneus distinguishes himself in battle. The fighting is furious on both sides. The Greeks rout the Trojans, and Ajax knocks out Hector with a huge stone. Hera seduces Zeus to divert his attention from the Greeks’ success. When Zeus awakens, he aids Hector and the Trojans, and they advance all the way up to the Greek ships. Ajax alone holds the Trojans at bay as they attempt to burn one of the ships.

MEETING 9: books 16 and 17

After the vocabulary quiz, we will turn to Books 16 and 17, the turning point of the Iliad. Does the poem make clear why Achilles lets Patroclus go in his armor? Does it make sense to you? How might we explain it?

Sarpedon’s death is the first of four deaths in the Trojan legend that follows the same pattern: (1) Armor stripped, (2) Fight for the body, and (3) Divine intervention. Why?

In Book 17 we’ll want to explore two related moments: Zeus’s pity for Hector and his pity for Achilles’ weeping horses. What might be the connection between these two moments?

Homework: Read Books 18 and 19.

MEETING 10: books 18 and 19

Book 18 ends the longest day: Homer ends the day with a profound image of Achilles crowned with fire and amplified by the voice of the gods, the beginning of Achilles’s apotheosis. During today’s class, we’ll look at Homer’s continued characterization of Achilles as something inhuman; that is to say, we’ll look at why Homer makes Achilles both subhuman and superhuman at once.

Let’s begin by looking at the top of 356. What does grief do to Achilles? To what extent does Achilles die a kind of death in this passage? What does the grief turn to on 358? Compare to 171. And finally, look to 361 to see what Achilles is rewarded with after he embraces his own mortality.

In the second half of class we’ll look at a lyric poem by Patrick Shaw-Stewart that begins with the line, “I saw a man this morning.” How does Shaw-Stewart use this famous moment in the Iliad to cope with his own mortality during WW1? Let’s then turn to the cover of our edition of Homer’s poem.

Why is Achilles’s armor fashioned in the way that it is?

Homework: Enjoy Books 20 and 21.

MEETING 11: FRQ3 Introduction and Practice

Today we will introduce the literary argument essay, its form and the way it’s assessed. We’ll begin here with a smattering of prompts from years past.

Then we’ll take the 2017 prompt about mysterious origins and brainstorm together how we might use the Iliad to write a defensible response to that prompt. I have 3 sample essays from that year that we’ll grade together.

Finally, I’d like for you to work in your groups to develop a plan, using the Iliad, for an essay to one of two recent prompts.

Homework: Enjoy Books 22 and 23.

MEETING 12: books 22 and 23

A few housekeeping matters to take care of at the beginning of class today: (1) AP Classroom, (2) Reminders of the upcoming schedule, and (3) Iliad Essay

Books 22 and 23: What does Homer achieve in comparing Hector to Achilles throughout the Iliad? How does Book 22 build to a climax in relation to their contrast? We’ll begin with Zeus’s scales, bring all our knowledge of Hector and Achilles to bear, and then compare three moments in Book 22.

What is the purpose of having Patroclus appear to Achilles in Book 23?

We’ll end class today with a practice MCQ set.

Homework: Enjoy Book 24. Prepare for Vocabulary Quiz 6. Read through the Iliad Process Essay Packet.

MEETING 13: book 24

We begin today with the vocabulary quiz. After:

Show that Achilles’s decision to return Hector’s body to Priam makes sense. You must use to support your point the following scenes:

The visit of Patroclus’s spirit in Book 23

Apollo’s address to the immortals in Book 24

Thetis’s visit to Achilles in Book 24

Priam’s plea in Book 24

Trace that sequence. What does Homer want you to see?

due DATES

FALL FINAL EXAM

Part A: Iliad Process Essay, 50% of Final Exam + 1 Major Grade (11/27)

Part B: Modified AP Exam, 50% of Final Exam

(1) In-Class Prose Analysis (30 points) (12/7, 12/8)

(2) 40 MC Questions (40 points) (12/18)

(3) Poetry Analysis (30 points) (12/18)

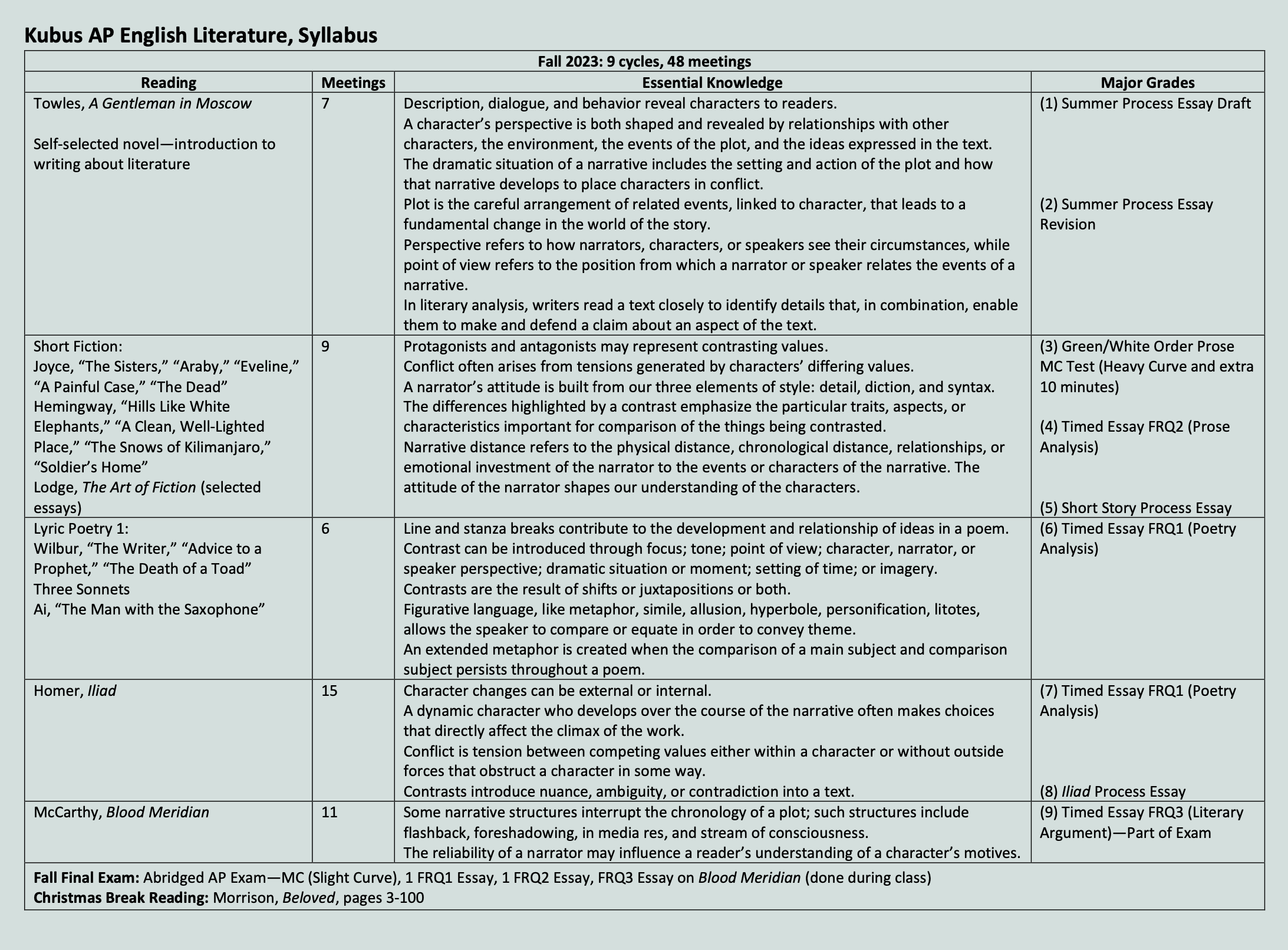

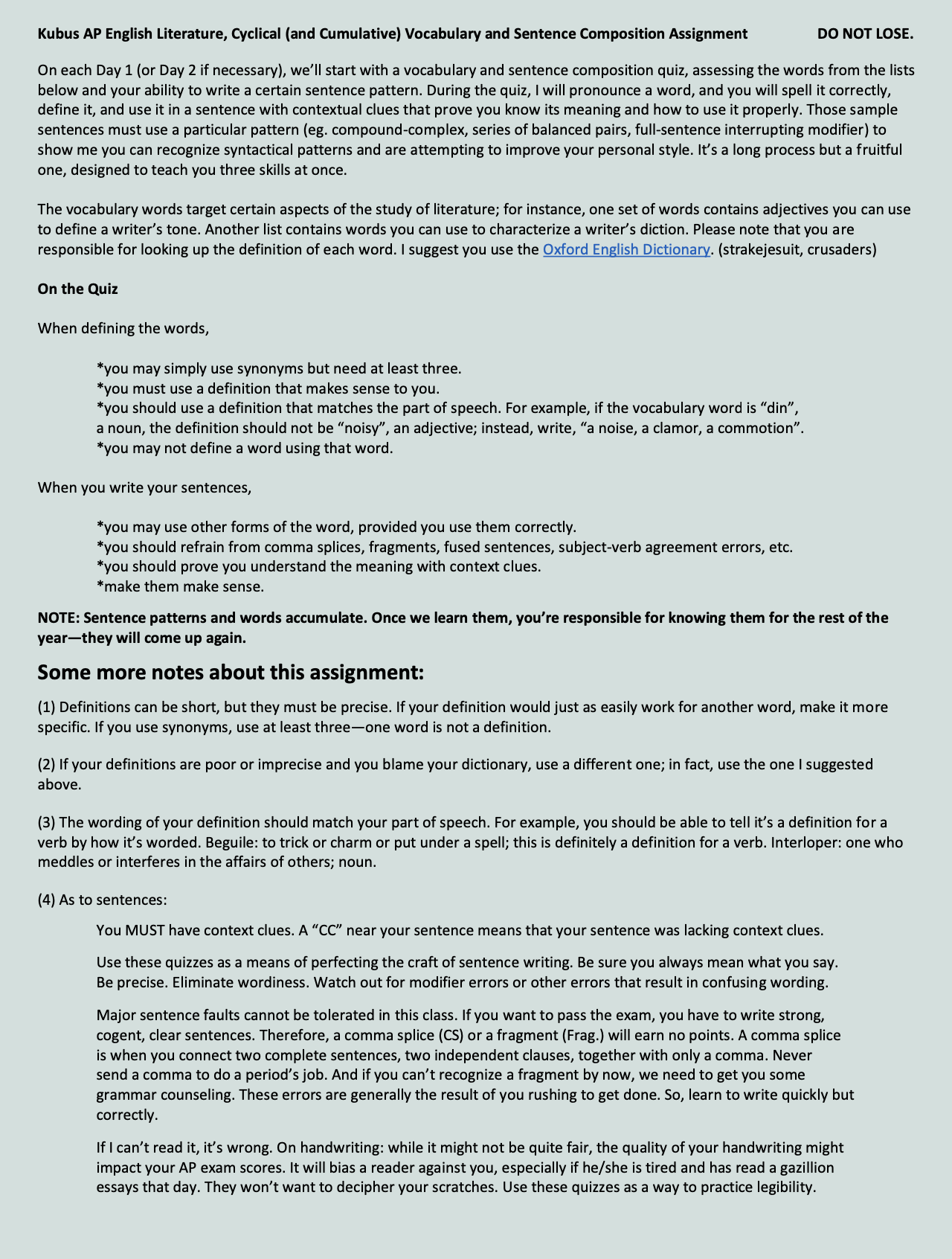

CURRENT TEXTs TO HAVE DAILY

syllabus

cyclical vocabulary and sentence composition assignment

HOMER’S ILIAD STUDY LINKS

The Iliad may be ancient – but it’s not far away

New York Times review of Lombardo's translation of the Iliad

Parallels between ISIS and warriors in the Iliad?

Can Homer's Iliad speak across the centuries?

Book by book outline of the events of the poem

A Study Guide from Duke University with a list of the principal episodes

A more detailed version of the above study guide

Early Greek Humanism: The Beauty of the Human Form and Essence

Columbia's historical context for Homer

Guide to reading the Iliad with notes on epic and the heroic world

2023-2024 units

writing assignments

2022-2023 UNITS

war and peace central

It seems even Tolstoy didn’t quite know what War and Peace is: “It is not a novel,” he said, “still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle. War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express, in the form in which it is expressed.” And yet, it’s the first title we think of when we think of some of the greatest or most famous novels ever written. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s innovative: it plays with multiple languages, moves from battlefields to palaces to country estates, combines historical figures like Napoleon and Kutuzov with fictional characters like Bolkonsky and Rostov, folds in bloody battles to scenes of great personal strife and triumph, and changes narrators at will. That’s innovation. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s human: Tolstoy writes no archetypes, but people; no heroes, but soldiers; no villains, but sinners; no pillars of grace, but kind-hearted, flawed characters. That’s human. And whatever War and Peace is, it’s big: With almost 600—yes, 600—named characters, more than 1300 pages, multiple shifts in narrative voice, oscillations between scenes of aristocratic drama and the history of the Napoleonic Wars and some of Tolstoy’s personal philosophy, it’s no wonder Henry James famously called War and Peace “a big, loose, baggy monster.”

Once a month, a small group of us will have a meeting to discuss the next section of the novel, spending a few consecutive days after school with conversation, food, and drink. I hope it’ll be something you really enjoy despite the obstacles of the novel. But don’t let those obstacles prevent you from working through it. Look, I get it: the names are hard, and like I said, there are a lot of them. And look, I get it: Looking at the footnotes to translate the French is annoying. And look, I get it: there are some parts that are just plain dull. It’s okay. Sometimes long-form fiction will be like that. But you’ll do your work, anyway, like the great student and person you are. There are many reasons to set this book down and move on with your life, but there are more reasons—some you may not understand for a few years—to continue working your way through. It’s a work of art filled with beautiful characters, intricately woven threads of plot, thrilling scenes, compelling relationships, people to root for and against. The natural barriers of the novel are nothing compared to the reward on the other side. You’ll be just fine—better than fine, really. And you’re reading in a community of like-minded readers with great opinions to encourage you through it.