unit 7, shakespeare’s king lear

meeting 1: the beginning of king lear

King Lear is a unique play among Shakespeare’s tragedies in many ways as we’ll see. The first way in which it is unqiue is that it is the only play (other than The Winter’s Tale) that begins with the play’s generic catastrophic moment: Why might the dramatist see this as valuable?

Cardinal DiNardo asked us to read the Gospel of Mark this Lent. Here’s a short passage: 20 Then Jesus entered a house, and again a crowd gathered, so that he and his disciples were not even able to eat. 21 When his family[b] heard about this, they went to take charge of him, for they said, “He is out of his mind.” 22 And the teachers of the law who came down from Jerusalem said, “He is possessed by Beelzebul! By the prince of demons he is driving out demons.” 23 So Jesus called them over to him and began to speak to them in parables: “How can Satan drive out Satan? 24 If a kingdom is divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand. 25 If a house is divided against itself, that house cannot stand. 26 And if Satan opposes himself and is divided, he cannot stand; his end has come. 27 In fact, no one can enter a strong man’s house without first tying him up. Then he can plunder the strong man’s house. 28 Truly I tell you, people can be forgiven all their sins and every slander they utter, 29 but whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit will never be forgiven; they are guilty of an eternal sin.”

Each great scene in a play will revolve around a central conflict. The central conflict in 1.1 is Lear’s desire to give up power but inability to give up all of the things that come with power.

Homework: Finish Othello Essay.

MEETING 2: comedy/tragedy & 1.1-1.3

Mosaic depicting theatrical masks of Tragedy and Comedy, 2nd century AD, from Rome, Palazzo Nuovo

Today, after we exchange essays, we’ll discuss Shakespeare’s genres. Comedy and tragedy don’t merely delineate happy and sad; more precisely, comedy and tragedy refer to the narrative structure of a play, the way in which the play’s dramatic conflicts resolve. A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet are largely the same play, but one is a comedy and one is a tragedy because of the way the conflicts resolve: If Juliet wakes 30 seconds earlier, the play is a comedy; if the lovers don’t discover they’ve been in love with the wrong person, they just might die. Comedies end happily in marriage; tragedies end unfortunately in death. Shakespeare, however, knows that good drama blurs of the lines of these genre and uses elements of each in many of his plays.

Why is Lear so cruel to Cordelia in the second half of 1.1? Is he being petulant by throwing the word “nothing” back at Cordelia, or is it coincidence?

What does Cordelia have to say about flattery and lying in her speech on page 15? And what of her prophetic line to her sisters: “Time shall unfold what plighted cunning hides;/Who covers fault, at last with shame derides”?

Homework:

I’d like you to try your hand at finishing the next scene, Act 1 scenes 2 and 3. Prepare them for our next class. While reading, think about how Edmond and Edgar’s dialogue compares to Gonerill and Regan’s dialogue in the previous scene. If you want also to watch the Royal Shakespeare Company production, you may log in to Drama Online Library with strakejesuit, crusaders. It will help to watch the scene. It begins at 18:45.

MEETING 3: SHAKESPEARE’S FOOLS & 1.2-1.5

1.2: What parallels do you see between 1.1 and 1.2? How does Edmond manipulate his father so quickly? Is it believable that he might be convinced so quickly?

1.4: We’ll talk today about the convention of the Fool in Shakespeare’s plays with particular focus on the license they have to criticize the behavior of those they serve. In his first scene the Fool makes about 25 jokes, many of them puns, all of them intended to show Lear’s mistakes. There seem to be 4 subcategories of criticism:

1) It was stupid to give up power and wealth. 2) It was really counterproductive to have banished Cordelia. 3) It was dumb to put yourself at the mercy of your evil daughters. 4) It was all caused by the fact that you act without thinking.

What’s the difference between the loyalty of the Fool and the loyalty of Kent?

How have your sympathies for Lear changed, if at all, by the end of the Act?

Homework:

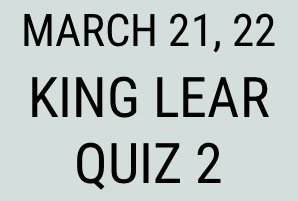

Prepare for the first Lear quiz.

MEETING 4: ACT 1 Quiz and REVIEW

After we finish 1.4 and 1.5, you’ll take your first King Lear quiz.

Homework:

For our next class, read Act 2, scenes 1 and 2. We’ll review those scenes briefly at the beginning of our next class, which is a chavrusa day.

MEETING 5: THE BEDLAM BEGGAR & 2.3-2.4

Sit today with your CHAVRUSA.

(1) 2.1, 2.2: What’s your reaction to Edgar? How might we explain his quick departure?

How does Edmond incorporate Cornwall’s arrival as well as the growing divide between him and his brother-in-law?

What’s your favorite Kentian insult?

Examine 2.2.63-75: Why, according to Kent, is Oswald the worst kind of person?

(2) 2.3: First, I’ll set the context for Edgar’s means of hiding. What strikes you about the first of Edgar’s many soliloquies?

(3) 2.4.1-117: 2.4 is in my top 10 scenes from Shakespeare’s plays. It’s an extraordinarily sad descent into madness. Let’s read the first half before pausing to think it through.

(4) 2.4.118-end: We need to decipher whether Lear himself is or Gonerill and Regan are to blame for his descent. Does Lear make things worse for himself? Why is there a storm in the background?

Homework:

Finish reading Act 2 and 3.1.

MEETING 6: 3.2

One of Shakespeare’s most famous scenes, 3.2, depicts the weather mirroring Lear’s madness. Why is that particularly appropriate given what many characters argue about nature?

How is the fool different in 3.2 than he was before? What do we learn in this scene about the nature of his foolery?

There are three parts of Lear’s diatribe in 3.2. We’ll move through all three today in class before watching our production’s version of the scene.

Homework:

Finish reading Act 3. Turn to page 132 in our text. Respond to exercise 3: Madness. Skip points 1 and 4. Do points 2 and 3: “Pick out…” and “Then choose…”.

MEETING 7: the play about nothing

We’ll begin on page 103: Note Lear’s call back to 1.1.

In the remainder of Act 3, Shakespeare begins alternating between Lear and Gloucester, the play’s two old men. What is Shakespeare’s dramatic intent in alternating these scenes as he does? What thematic point might he be trying to highlight?

Is there any intelligibility in the way Edgar manifests Tom’s madness?

At the end of class we’ll review some of the more important quotes from Acts 2 and 3.

We’ll then turn to the beginning of Act 4. Why does Edgar continue to keep his identity from his father?

Homework over spring break:

Read all of Act 4.

MEETING 8: recognitions, reunions, miracles

Who is vying for power in Britain at this point in the play? I think it’d be helpful to step back and first consider the various narrative threads and how they’re tangling.

Scenes 5 and 6 of King Lear stand tall above most other scenes in the history of drama not only for their emotional impact but also for the contrast they draw toward one another. Of course they are both scenes of recognition, of knowing again, of becoming reacquainted, but what do you see as the key distinctions between the recognitions of Gloucester/Edgar (even though Gloucester doesn’t quite know entirely who Edgar is), Lear/Gloucester, and Lear/Cordelia? They are also scenes of miracles, of impossible reunions that take shape, or at least that’s how they’re framed in the text. What does Shakespeare want us to see in putting these two scenes right next to each other?

Sift through Lear’s madness. Find

(1) sorrow.

(2) humor.

(3) wisdom through suffering.

What’s the dominant emotion in King Lear when he first sees Cordelia? Is it shame? Is it joy? Why?

In the second half of class today, we’ll review FRQ1 and FRQ 2. You’ll find the notes to the right.

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Read 5.1 and 5.2. Leave the last scene for us to work through together in our next class.

Read the sample essays that received a 6 on the latest AP exam.

MEETING 9: Act 5 and more practice exam review

Samuel Johnson said of the final scene of King Lear that it’s too sad to perform. As we work through the scene, ask yourself why Johnson would’ve made this claim.

Do you think the Lear of Act 5 is too different from the Lear of Act 1? If not, what has it taken to get him from point A to point B?

In 5.3, after Cordelia’s first line, she’s silent for the rest of the play. Of this and the general treatment of Cordelia, scholar Kathleen McLuskie says, “Cordelia’s saving love, so admired by critics, works in the action less as a redemption for womankind than as an example of patriarchy restored.” What do you think? Does McLuskie have a point? Can the same rationale be applied to the poor and disabled—that is, does the fact that the poor lose their voice in the play simply restore the monarchy as it was at the beginning of the play? Do you think Shakespeare is conscious of this?

Kent asks near the very end of the play, “Is this the promised end?” Is it? Did Shakespeare break a contract? Is the sadness to much?

Are you satisfied with the political resolution of the play? Is it appropriate? Why or why not?

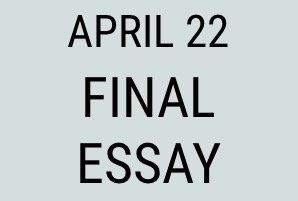

MEETING 10: practice exam review

This course invited you—to the extent you were willing—to slowly read a wide variety of literary texts written in or translated into English. We’ve read lyric poems, a narrative poem, novels, and short stories to see how literature reflects and comments on human experience. I set out—to the extent I was able—to show you how small sections of text (microliterature) provide us with an understanding of the entire work (macroliterature), and that in our writing, we use those small sections to build a thematic understanding of the work as a whole.

And so this year, we slowly and consistently layered in the study of sentence structures, paragraphs of analysis, holistic arguments and essays, and vocabulary, as well as sharpened our thinking skills by pushing each other to listen to each other’s thoughts in class and—in many cases—share with everyone what we think about and how we react to the texts we read. The hope is your vocabulary improved, your sentences improved, your paragraphs improved, your essays improved, your reading improved, your thinking improved, and most importantly, your understanding of why we read imaginative literature improved.

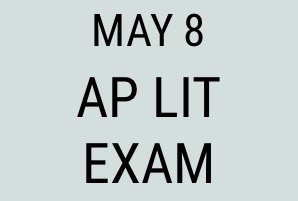

The Bureaucracy now wants to quantify what you learned, and I’d like you to show them to the best of your ability. You’ll do that by succeeding on the AP exam in May.

Review of the Exam Structure

Section I: Multiple-Choice 55 questions over 5 passages worth 45% in 1 hour

Usually there are 3 poems/poetry passages and 2 prose passages.

Section II: Free-Response 3 essays worth 55% in 2 hours

Poetry Analysis, Prose Analysis, Literary Argument

MC Tips from Albert.io

The following are important steps to answering AP® English Literature questions such as this example. Read through them, determine if you addressed this practice section correctly, then check your answers.

Read the entire sample; do not skim or read the questions first. This prevents you from making mistakes due to misunderstanding underlying themes. Read at a reasonable pace, as you are being timed.

Analyze the passage for tone, purpose, and use of literary devices. These are common questions for the AP® English Literature Exam and can be overlooked, easily.

Read questions carefully prior to answering. Be sure to read instructions as well as the answers to ensure you understand what is being asked.

Reread lines which are directly referenced in questions, e.g. line 7 in question 2 of our example. Before selecting your answer, reread the correlated line to confirm your choice.

Wisely divide your time to read each passage and provide your answers. Remember you have 60 minutes to complete a 55 question exam. If you’re stuck, and completely unsure, move on. Mark these sections so you can return once you’ve answered everything you’re confident of. If you are still wary, eliminate all the answers you can and guess from the remaining choices.

Notes along the page margins can be extremely helpful. As you read the text note context, tone, literary devices and any special points. Quickly jot these in the margin as you read. This will help you answer the questions quickly and efficiently.

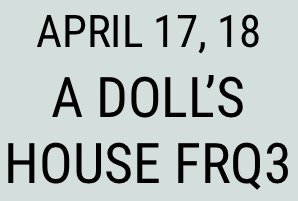

due DATES

CURRENT TEXTs TO HAVE DAILY

king lear: true or false?

(1) Taken out of context, Edgar’s line to his father, “Thy life’s a miracle,” states the argument of Shakespeare’s King Lear.

(2) Lear’s cognitive decline stems not from any physical malady.

(3) Edgar is the only character in King Lear to go mad.

(4) All but one or two characters in King Lear receive their just deserts.

(5) King Lear makes no distinction between Gonerill and Regan.

(6) No character in King Lear is wholly good or bad.

(7) In King Lear, human patience and the human capacity for love defeat “the forces of fortune, nature, and the indifference of the gods” (Kermode).

upcoming dates for reading groups

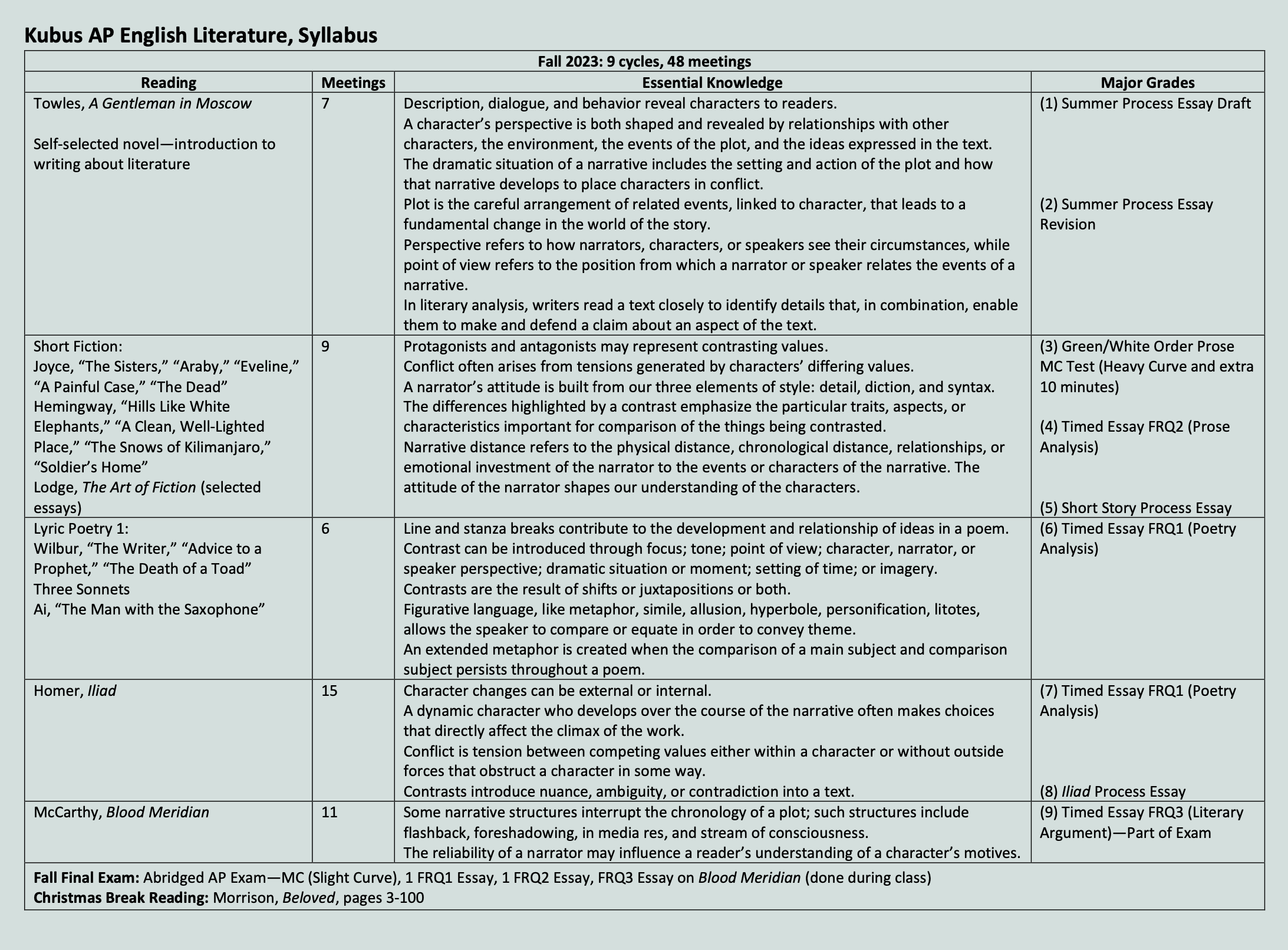

syllabus

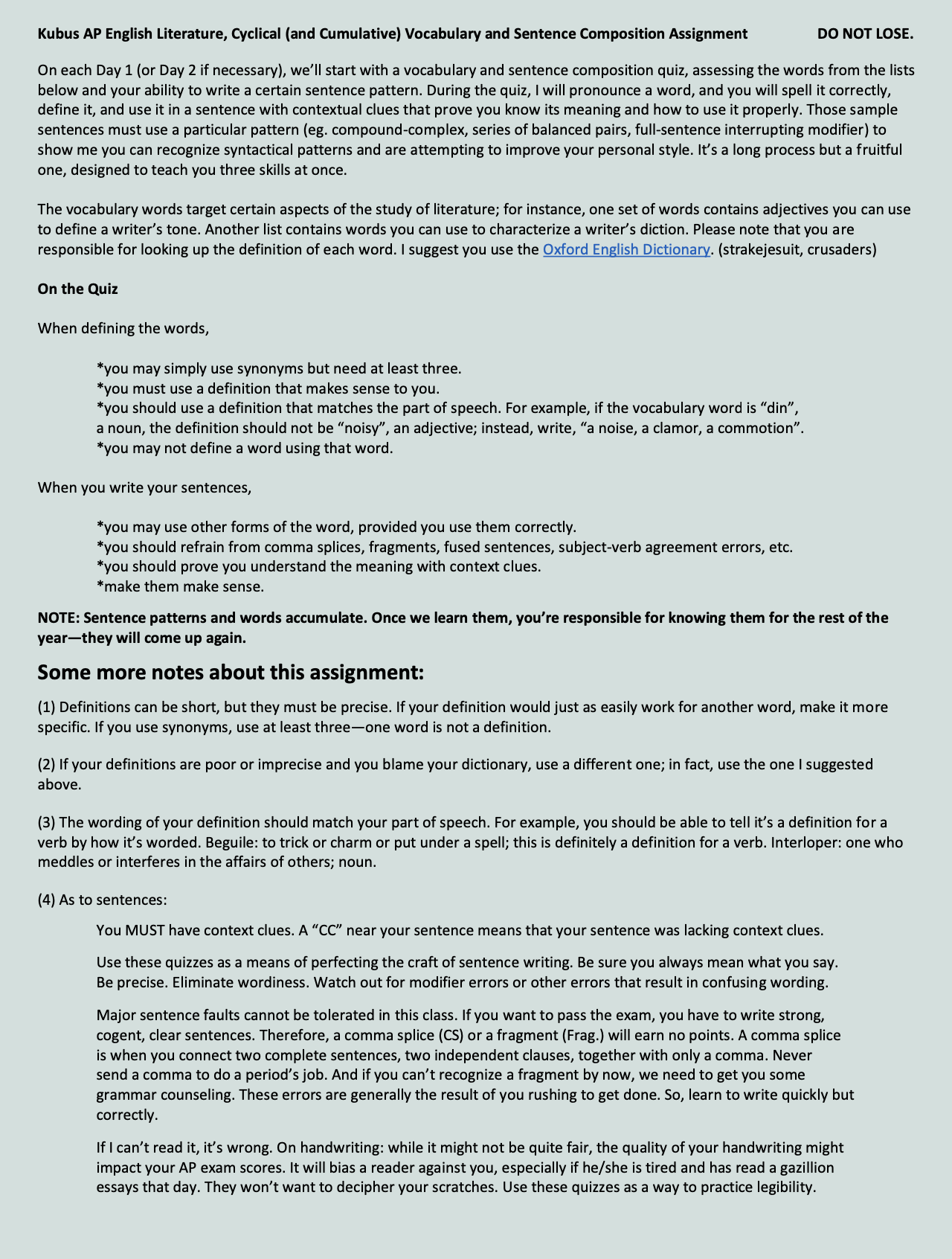

cyclical vocabulary and sentence composition assignment

2023-2024 units

writing assignments

2022-2023 UNITS

war and peace central

It seems even Tolstoy didn’t quite know what War and Peace is: “It is not a novel,” he said, “still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle. War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express, in the form in which it is expressed.” And yet, it’s the first title we think of when we think of some of the greatest or most famous novels ever written. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s innovative: it plays with multiple languages, moves from battlefields to palaces to country estates, combines historical figures like Napoleon and Kutuzov with fictional characters like Bolkonsky and Rostov, folds in bloody battles to scenes of great personal strife and triumph, and changes narrators at will. That’s innovation. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s human: Tolstoy writes no archetypes, but people; no heroes, but soldiers; no villains, but sinners; no pillars of grace, but kind-hearted, flawed characters. That’s human. And whatever War and Peace is, it’s big: With almost 600—yes, 600—named characters, more than 1300 pages, multiple shifts in narrative voice, oscillations between scenes of aristocratic drama and the history of the Napoleonic Wars and some of Tolstoy’s personal philosophy, it’s no wonder Henry James famously called War and Peace “a big, loose, baggy monster.”

Once a month, a small group of us will have a meeting to discuss the next section of the novel, spending a few consecutive days after school with conversation, food, and drink. I hope it’ll be something you really enjoy despite the obstacles of the novel. But don’t let those obstacles prevent you from working through it. Look, I get it: the names are hard, and like I said, there are a lot of them. And look, I get it: Looking at the footnotes to translate the French is annoying. And look, I get it: there are some parts that are just plain dull. It’s okay. Sometimes long-form fiction will be like that. But you’ll do your work, anyway, like the great student and person you are. There are many reasons to set this book down and move on with your life, but there are more reasons—some you may not understand for a few years—to continue working your way through. It’s a work of art filled with beautiful characters, intricately woven threads of plot, thrilling scenes, compelling relationships, people to root for and against. The natural barriers of the novel are nothing compared to the reward on the other side. You’ll be just fine—better than fine, really. And you’re reading in a community of like-minded readers with great opinions to encourage you through it.