unit 8, ibsen’s a doll’s house

MEETING 1: IBSEN AND THE WELL-MADE PLAY

The theory of the well-made play:

(1) The plot revolves around a secret held by the protagonist; the secret is known to the audience but withheld from key characters.

(2) The plot is driven by scenes of increasing intensity and suspense. The play is usually a slow, slow, deliberate burn.

(3) The plot contains (too) perfect, almost contrived—even twee—entrances and exits and requires handy devices like letters or telegrams to move it forward.

(4) The secret stems from a conflict with one or more of the play’s other characters.

(5) The plot contains peripeteia in a dramatic scene at the end that exposes the secret.

Ibsen’s drama:

(1) Makes taboo acceptable

(2) Discards soliloquies and asides

(3) Contains motivated exposition

(4) Environment influences the personalities of the characters

(5) Takes nothing for granted

(6) Usually has a thesis in a way Shakespeare does not

Today we’re going to look predominantly at the actions of the first part of Act 1, thinking about how they provide us with all we need to know about Nora.

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Read Pages 17-34.

MEETING 2: KROGSTAD TURNS THE SCREWS

Before moving into the new reading, let’s think about the first iteration of one of the play’s central questions that Nora raises a number of times: “Is it rash to save your husband’s life?” (14). Is Nora right? Does she have the moral high ground? What are the assumptions in this question? Let’s watch the 2012 production’s version of this scene [16:00-29:00].

I’d like to focus most of our time today on the first scene between Nora and Krogstad. In what ways are Nora and Krogstad alike? different?

KROGSTAD. The law takes no account of motives.

NORA. Then they must be very bad laws.

KROGSTAD. Bad or not, if I produce this document in court, you’ll be condemned according to them.

NORA. I don’t believe it. Isn’t a daughter entitled to try and save her father from worry and anxiety on his deathbed? Isn’t a wife entitled to save her husband’s life? I might not know very much about the law, but I feel sure of one thing: it must say somewhere that things like this are allowed. You mean to say you don’t know that—you, when it’s your job? You must be a rotten lawyer, Mr. Krogstad.

They’re both right, and they’re both wrong, no? [33:45-43:41]

Nora and Helmer: “A fog of lies like that in a household, and it spreads disease and infection to every part of it. Every breath the children take in that kind of house is reeking with evil germs” (33). What does Torvald inadvertently do to Nora? [43:41-52:00]

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Read pages 35-61.

MEETING 3: NORA’S DOLL HOUSE

SIT TODAY WITH YOUR CHAVRUSA.

Sample Secondary Source Search

We should review some of the takeaways from our last class: A Doll’s House is not King Lear, but is it the stuff of tragedy? Why? Nora and Krogstad find themselves in similar circumstances early on in the play, but we sympathize with Nora. Why?

The 2012 production of A Doll’s House literally revolves around Nora, emphasizing how stationary she remains while everyone else comes and goes. Let’s think about the play like that: Each secondary character has their turn to play with Nora—Helmer, Anne Marie, Rank, Mrs. Linde, and Krogstad. Why is the architecture of the play designed like this? Does each character play with Nora to cope with their own insecurities? Why? Does it matter that they’re all professionals of some sort?

Consider each of these scenes in the second act:

Nora and Anne Marie: What is the dramatic function of this scene? [51:32]

Nora and Mrs. Linde: What do we learn about Dr. Rank?

Nora and Helmer: “I forgive you.” [1:03:25]

Nora and Rank: What does Dr. Rank understand about Nora’s intentions in this scene?

Nora and Krogstad: “Courage.” [1:22:00]

Nora and Mrs. Linde: What’s the “miracle”?

Nora and Krogstad, Part 2: Nora and Krogstad throw the word courage back and forth between each other. How does the meaning of the word change each time it’s uttered? What makes an action courageous or uncourageous, does the play suggest? Choose only one character to develop your thinking.

What is Ibsen’s intent in having Nora dance the tarantella at the end of Act 2?

HOMEWORK FOR OUR NEXT CLASS:

Finish the play!

MEETING 4: a divided duty

On page 83, Nora argues that her duty to herself as an individual is just as sacred as the duty she has to her family and to her community. Do you agree? Why or why not? Are you put off by Nora’s decision at the end of the play? Does Ibsen do enough to convince you that Nora makes the correct decision?

Gregory Doran, the former Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, says that some playwrights will “stare with a very steady eye at some of the elements in our make-up which are ugliest.” Does Ibsen? What ugly elements of our make-up does he see, and what does the play suggest about the extent we can change them?

MEETING 5: sample research essays

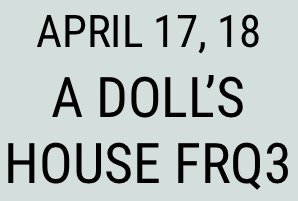

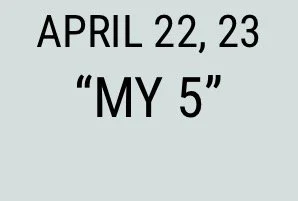

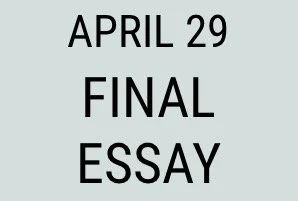

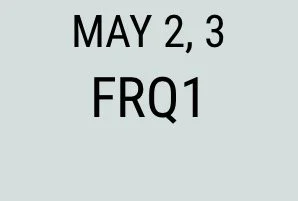

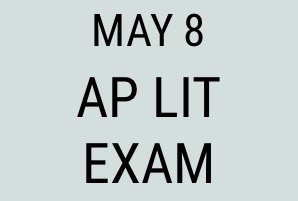

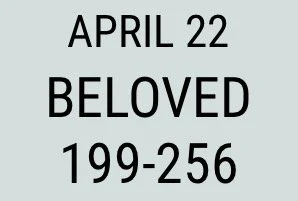

due DATES

CURRENT TEXTs TO HAVE DAILY

upcoming dates for reading groups

KEY QUESTIONS FOR A DOLL’S HOUSE

[A] In his review of the 2012 Young Vic production, New York Times critic Ben Brantley writes, “Nora is forced into devastating awareness of just how devious she’s become and how warped she has been by the subterfuge.” Write an essay that explores the extent to which Nora is forced into this awareness. Who forces her? Or is it an undoing she must own? What is the play’s greater idea about deceit?

[B] Choose one of the characters in the play. Trace that character’s understanding of and write an essay about what makes a fulfilled life in the eye of that character.

[C] Gregory Doran, the Artistic Director of the Royal Shakespeare Company, says that some playwrights will “stare with a very steady eye at some of the elements in our make-up which are ugliest.” Does Ibsen? What ugly elements of our make-up does he see, and what does the play suggest about the extent we can change them?

[D] One of the play’s great mysteries to me is why Torvald is so quick to forgive Nora after Krogstad returns the IOU. How do you explain his sudden reversal? You should use this prompt to discover some of Torvald’s more unattractive traits.

[E] Ibsen is famous for his artistic use of props. Write an essay that analyzes props and their artistic use in A Doll’s House. How are those props more than mere objects?

[F] The word “courage” repeats in the play, becoming associated with Mrs. Linde, Helmer, and Nora. What makes an action courageous or uncourageous, does the play suggest? Choose only one character to develop your thinking.

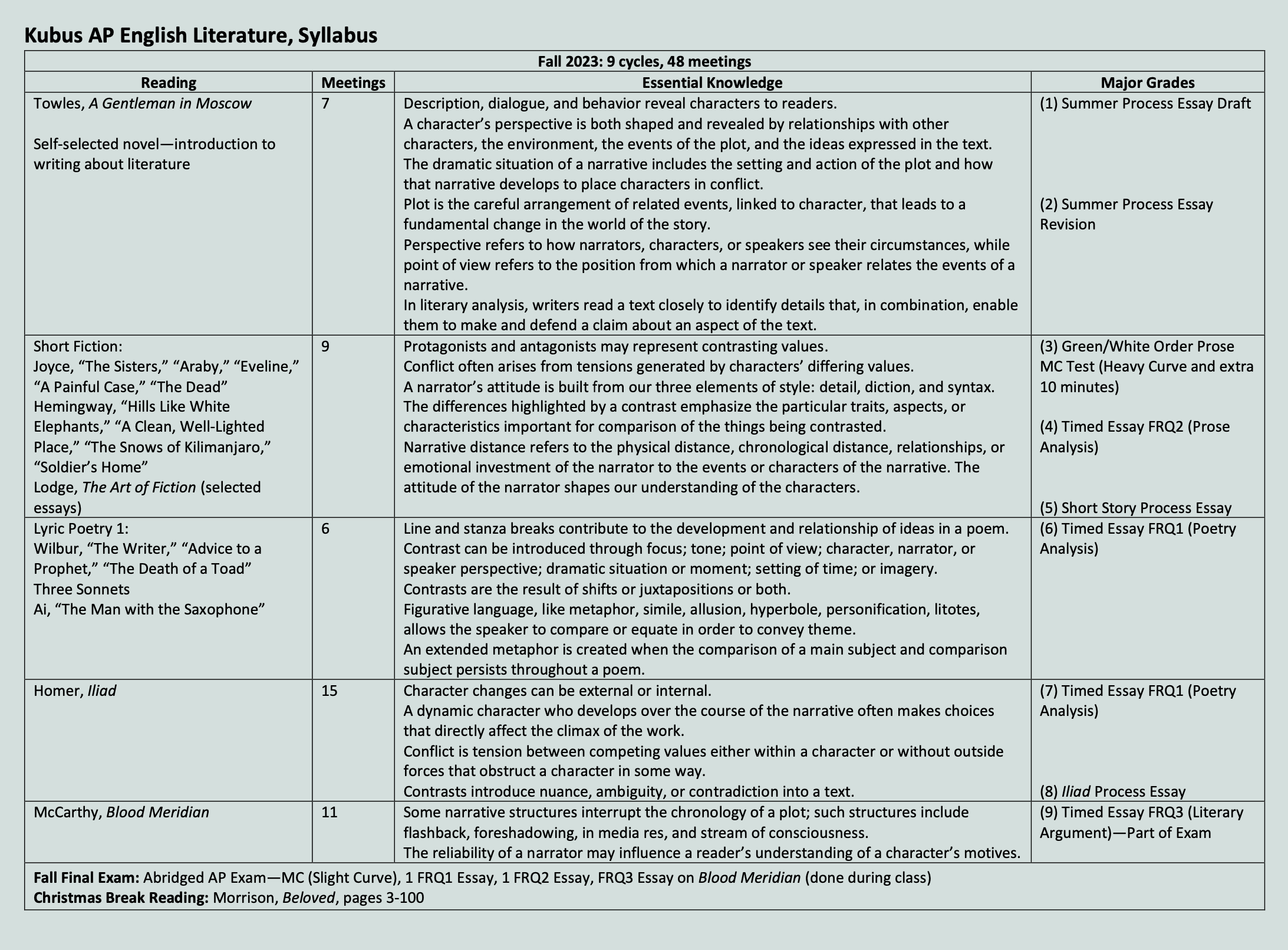

syllabus

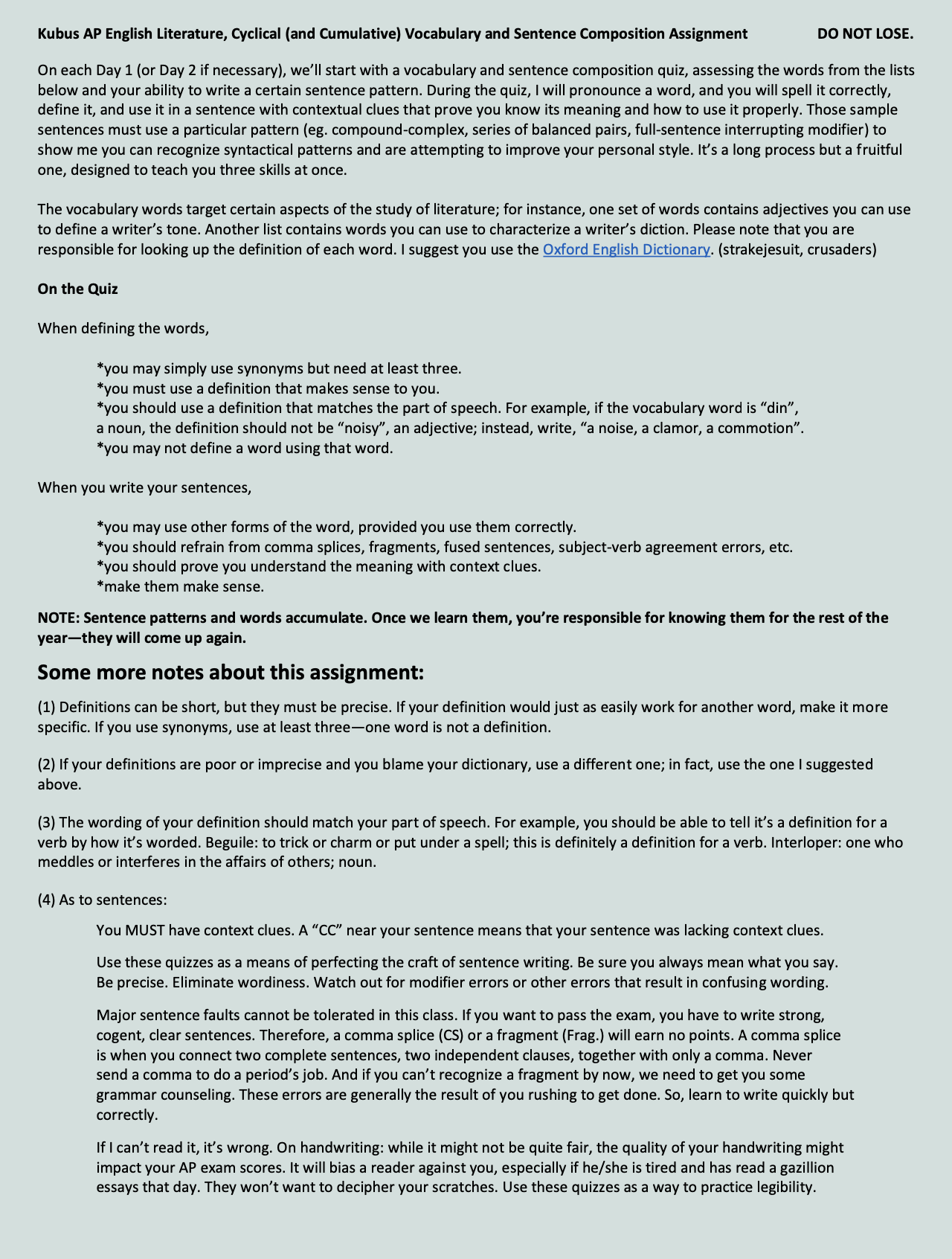

cyclical vocabulary and sentence composition assignment

2023-2024 units

writing assignments

2022-2023 UNITS

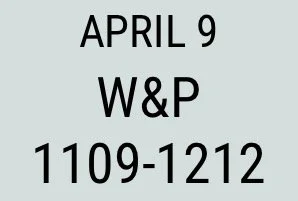

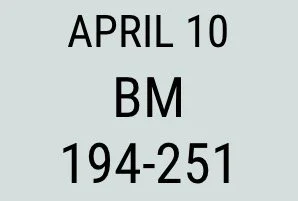

war and peace central

It seems even Tolstoy didn’t quite know what War and Peace is: “It is not a novel,” he said, “still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle. War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express, in the form in which it is expressed.” And yet, it’s the first title we think of when we think of some of the greatest or most famous novels ever written. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s innovative: it plays with multiple languages, moves from battlefields to palaces to country estates, combines historical figures like Napoleon and Kutuzov with fictional characters like Bolkonsky and Rostov, folds in bloody battles to scenes of great personal strife and triumph, and changes narrators at will. That’s innovation. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s human: Tolstoy writes no archetypes, but people; no heroes, but soldiers; no villains, but sinners; no pillars of grace, but kind-hearted, flawed characters. That’s human. And whatever War and Peace is, it’s big: With almost 600—yes, 600—named characters, more than 1300 pages, multiple shifts in narrative voice, oscillations between scenes of aristocratic drama and the history of the Napoleonic Wars and some of Tolstoy’s personal philosophy, it’s no wonder Henry James famously called War and Peace “a big, loose, baggy monster.”

Once a month, a small group of us will have a meeting to discuss the next section of the novel, spending a few consecutive days after school with conversation, food, and drink. I hope it’ll be something you really enjoy despite the obstacles of the novel. But don’t let those obstacles prevent you from working through it. Look, I get it: the names are hard, and like I said, there are a lot of them. And look, I get it: Looking at the footnotes to translate the French is annoying. And look, I get it: there are some parts that are just plain dull. It’s okay. Sometimes long-form fiction will be like that. But you’ll do your work, anyway, like the great student and person you are. There are many reasons to set this book down and move on with your life, but there are more reasons—some you may not understand for a few years—to continue working your way through. It’s a work of art filled with beautiful characters, intricately woven threads of plot, thrilling scenes, compelling relationships, people to root for and against. The natural barriers of the novel are nothing compared to the reward on the other side. You’ll be just fine—better than fine, really. And you’re reading in a community of like-minded readers with great opinions to encourage you through it.