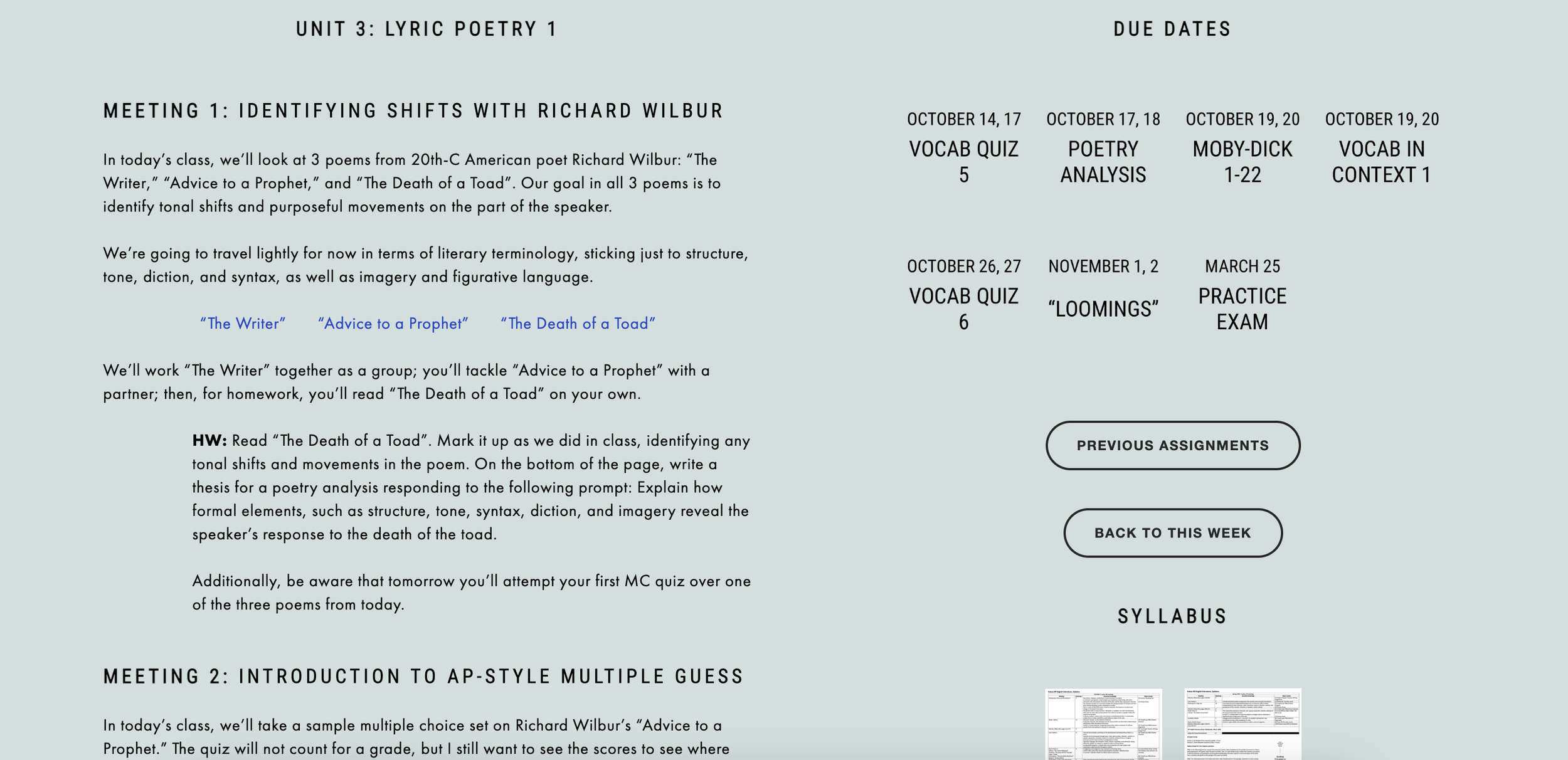

Last semester we developed a tripartite system for approaching a poem for the first time: Look at the (1) Speaker and conflict, (2) Shifts and movements, and (3) Devices and interpretations. This is a good plan for organizing your preparation for a poetry analysis.

This unit we’re going to look at poems that might seem a bit harder than the ones we studied in the fall—these are poems with more challenging conceits, with archaic diction and syntax, with more rigid and formal structures and schemes.

So, what are some strategies for dealing with a more difficult poem?

(1) Train your brain to notice repetitions: sound patterns, rhythms, images, rhymes, or ideas. How do these repetitions affect the reader’s impressions of the speaker and the poem’s ideas? Also, take note of when the speaker breaks repetitions; often, these occur at places where the poet packs away something important.

(2) Train your brain to sense tonal shifts, and draw a line to indicate that shift. We covered this last semester, but it cannot be overstated how important it is to notice movements in a poem.

(3) Separate the poem into thoughts, which will be arranged around full stops. Mark where all of the thoughts break and see if you can paraphrase each thought as simply as you can.

(4) Where you see a series of pronouns with unclear referents, draw an arrow to the antecedent to make more clear the subjects and objects of the poem.

(5) Don’t be afraid of thy’s, thou’s, and thine’s. It’s nothing more than the informal second person pronoun. You’re a Crusader; don’t cower.

Let’s practice these with two John Donne poems: “The Flea” and “The Good Morrow”.

MEETING 2: john Donne, part 2

SIT TODAY WITH YOUR CHAVRUSA.

Today is the final chavrusa day of the year. I hope you’ve had the opportunity to get to know your partner in the reading and discussing of a variety of stories and poems throughout the year.

Today we’ll work with two more of John Donne’s poems, “The Sun Rising” and “The Canonization”. Our focus today will be on the answering of MCQs. You’ll use the poetry question stems to write two of your own. In the second half of class, you and your chavrusa will answer an MCQ set together.

MEETING 3: donne, shakespeare, sidney

At the beginning of today’s class, I’m going to have you take an MCQ set on John Donne’s poem “The Canonization”. No stakes here. Just more practice before next week.

After, we’ll review sonnets by looking at Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 29” and one of Sidney’s sonnets. You’ll use this poetry data sheet to teach your poem to someone who studied the other poem.

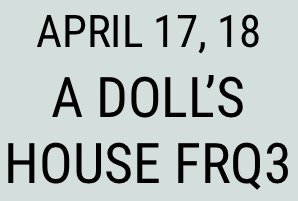

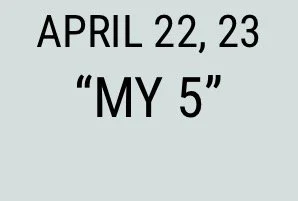

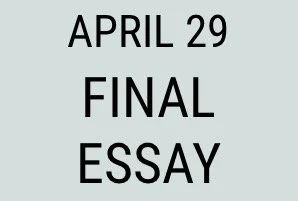

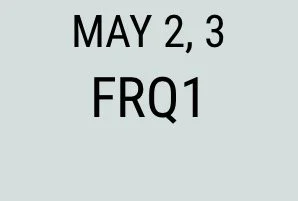

due DATES

CURRENT TEXTs TO HAVE DAILY

upcoming dates for reading groups

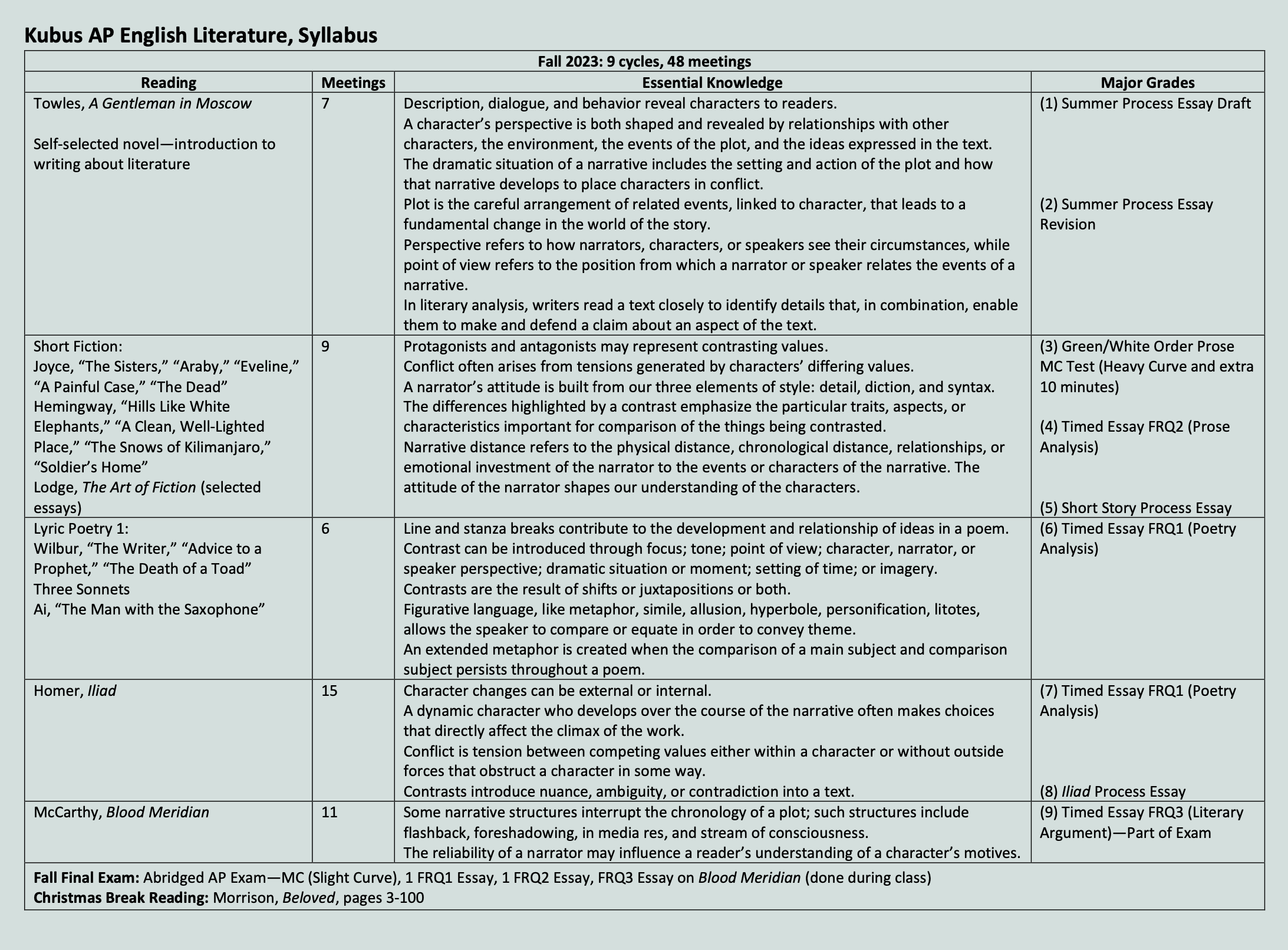

syllabus

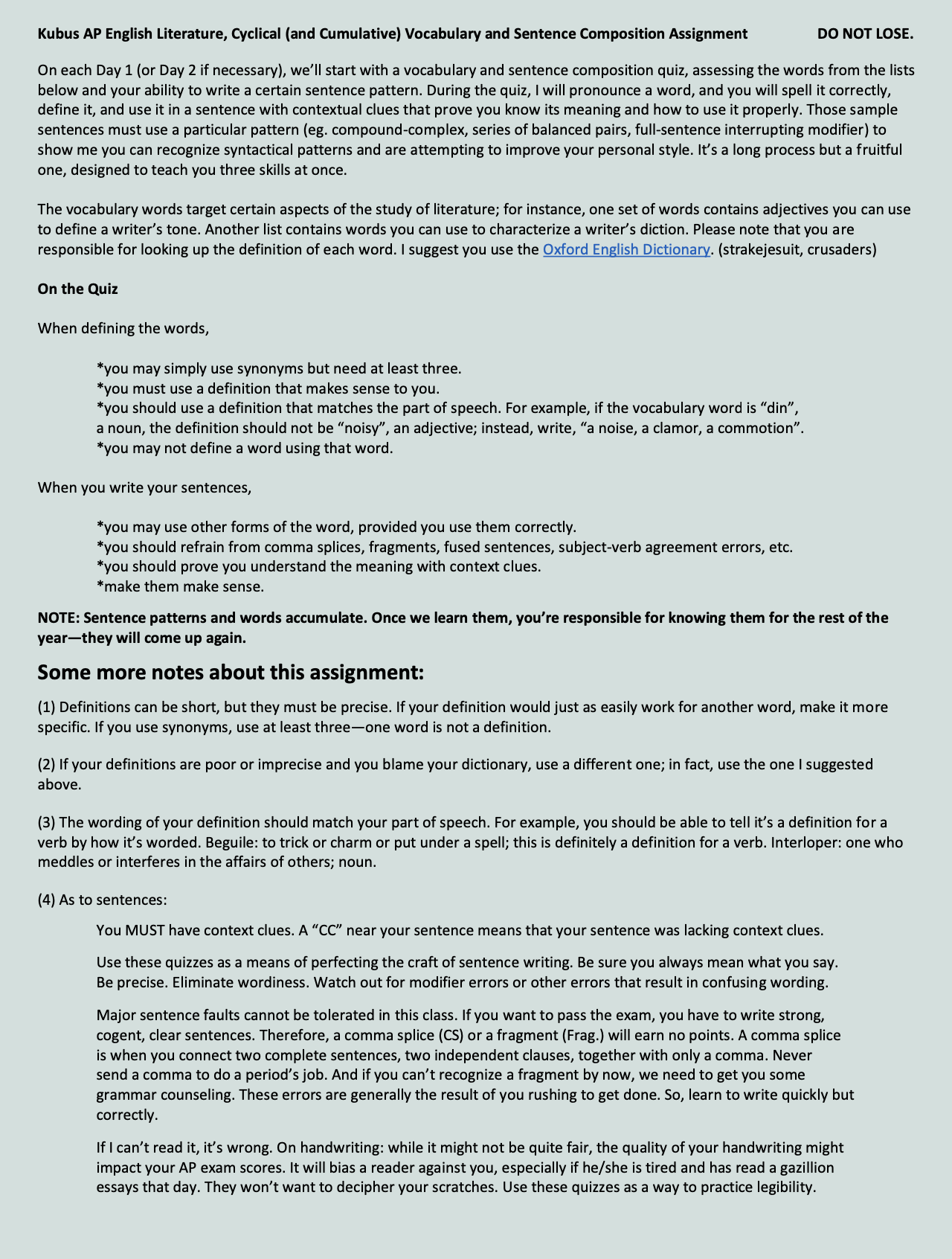

cyclical vocabulary and sentence composition assignment

2023-2024 units

writing assignments

2022-2023 UNITS

war and peace central

It seems even Tolstoy didn’t quite know what War and Peace is: “It is not a novel,” he said, “still less an epic poem, still less a historical chronicle. War and Peace is what the author wanted and was able to express, in the form in which it is expressed.” And yet, it’s the first title we think of when we think of some of the greatest or most famous novels ever written. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s innovative: it plays with multiple languages, moves from battlefields to palaces to country estates, combines historical figures like Napoleon and Kutuzov with fictional characters like Bolkonsky and Rostov, folds in bloody battles to scenes of great personal strife and triumph, and changes narrators at will. That’s innovation. Whatever War and Peace is, it’s human: Tolstoy writes no archetypes, but people; no heroes, but soldiers; no villains, but sinners; no pillars of grace, but kind-hearted, flawed characters. That’s human. And whatever War and Peace is, it’s big: With almost 600—yes, 600—named characters, more than 1300 pages, multiple shifts in narrative voice, oscillations between scenes of aristocratic drama and the history of the Napoleonic Wars and some of Tolstoy’s personal philosophy, it’s no wonder Henry James famously called War and Peace “a big, loose, baggy monster.”

Once a month, a small group of us will have a meeting to discuss the next section of the novel, spending a few consecutive days after school with conversation, food, and drink. I hope it’ll be something you really enjoy despite the obstacles of the novel. But don’t let those obstacles prevent you from working through it. Look, I get it: the names are hard, and like I said, there are a lot of them. And look, I get it: Looking at the footnotes to translate the French is annoying. And look, I get it: there are some parts that are just plain dull. It’s okay. Sometimes long-form fiction will be like that. But you’ll do your work, anyway, like the great student and person you are. There are many reasons to set this book down and move on with your life, but there are more reasons—some you may not understand for a few years—to continue working your way through. It’s a work of art filled with beautiful characters, intricately woven threads of plot, thrilling scenes, compelling relationships, people to root for and against. The natural barriers of the novel are nothing compared to the reward on the other side. You’ll be just fine—better than fine, really. And you’re reading in a community of like-minded readers with great opinions to encourage you through it.